In its most recent gruesome video, ISIS made 22 of its members behead what they claimed was a group of Syrian army officers and pilots. But this time, with the notable exception of British leader Jihad John, the executioners showed their faces. At least one of them was Asian. Some others were white. Two French citizens are thought to be in that video, among other nationalities.

The message was clear: ISIS has an army of global fighters who will threaten every country in the world. Since ISIS captured Mosul in June, most of the world governments have raised alarms over the threat those fighters can cause to their countries when they return home. In the Middle East, ISIS established active branches in Algeria, Libya, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia.

The threat has already become a reality. In Algeria, ISIS followers beheaded a French citizen in September 2014. In Libya, they control the town of Derna. In Egypt, they are engaged in a guerrilla war with the Egyptian state in Sinai that has claimed the lives of hundreds of security forces, insurgents, and civilians. In Saudi Arabia, they attacked Saudi Shiites and a Danish citizen in November.

Related: ISIS Beheads Another American As 60 New Terror Groups Join

In the west, an ISIS veteran of the Syrian war was behind the attack on a Jewish museum in Brussels in May that killed four people. Australian authorities foiled a plot to behead an Australian citizen on camera in September. British authorities stated in November that the threat from ISIS is the most dangerous to the U.K. since the 9/11 attacks. In the U.S., the FBI has just warned military service members that ISIS is planning to attack them at home.

Yet the full extent of how ISIS employed its foreign fighters was not told. Research conducted by the Terrorism Research and Analysis Consortium (TRAC) in Florida has shed some light on ISIS’s most valued asset and the important contribution foreign fighters have made to the rise of ISIS in Syria and Iraq. The research examines ISIS’s military units in Iraq and Syria, and explains how thousands of foreign fighters joined the Free Syrian Army to fight against the regime of Bashar al-Assad and shifted loyalty to al-Nusra front, al-Qaeda’s official branch in Syria, and then to ISIS.

Official estimates of ISIS’s size have varied widely. In September, the CIA stated that ISIS had between 20,000 to 31,500 fighters in Syria and Iraq. Another report stated that 2,000 Europeans and 100 Americans are fighting with ISIS. The United Nations Security Council has issued a report stating that 15,000 foreign fighters from 80 countries went to Syria to fight with ISIS and al-Nusra Front in 2013 and 2014, but this number doesn’t include fighters who were killed, returned to their countries, or who joined ISIS in another country, like Iraq. While the UN report noted that al-Qaeda’s central organization led by Ayman al-Zawahiri is struggling for relevance, organizations like ISIS are booming with fresh and young recruits. European countries like Germany, Britain and France have several hundred fighters in Syria, mostly fighting with ISIS. Some other Middle Eastern countries have thousands of fighters who went to Syria and ended up with ISIS.

“The IS [Islamic State] successes in Syria and Iraq is not a sole trajectory of the IS as a single force, but present a complex web of alliances with various brigades and foreign fighter groups. These alliances have enabled the IS to not only gain and capture areas, but also wield sustained controlled,” the TRAC research report states, using the acronym IS for ISIS.

By controlling cities, it gave foreign fighters irresistible temptation to join its ranks.

The report counts foreign military units (a unit could be a dozen fighters to thousands of them) from Libya (3), U.K. (all female fighters), Chechnya, Lebanon, Egypt, Dagestan (2), Indonesia, Germany (2), Tajikistan, Azerbaijan, Turkey, Belgium, Palestine, multinational Arab (2), and a multinational foreign unit.

Most of the foreign fighters came to Syria via the Turkish city of Antakya on the Syrian border. Most were recruited via mosques or online. Once a person has decided to join, he has to get a recommendation from a local cleric that ISIS or al-Nusra front trust. Then he would travel to Turkey pretending to be a tourist. Once there, he would cross the border – legally or illegally – and meet an ISIS representative who would take him to an ISIS guesthouse. Then he would start the training.

Tunisia is actually contributing the most foreign fighters to ISIS: no less than 2,000. Several reasons explain why the country that is the cradle of the Arab Spring and the only successful democracy has produced so many ISIS members. They include a high unemployment rate among the youth and a rise of Islamism in the country after a victory by the Muslim Brotherhood in the general election.

In late October 2014, Tunisian counter-terrorism forces raided a house in the capital and engaged in an armed clash with several militants, killing six of them and arresting 30 others. Five of the killed militants were college girls and some of them were trained in using weapons and fighting in Syria and Iraq. Tunisian writer al-Manji al-Saeedani says the investigations conducted by the Tunisian Ministry of Interior revealed that those young militants were attracted by Tunisian ISIS members who came from Syria and Iraq. Money and sex helped in the recruitment.

Another 19-year old boy seduced three girls, married them and recruited them. Each member was paid $1200 monthly, which is a lot of money for a student.

Unlike the expected norm of recruiting poor and ignorant youth, those who were killed were highly educated and not poor. One of the girls was a 20-year-old engineering student who was recruited by a female medical student. The engineering student recruited her sister, and both of them were killed in the clash. Another 19-year-old boy seduced three girls, married them, and recruited them. Each member was paid $1,200 monthly, which is a lot of money for a student. Six female leaders came back to Tunisia from Syria and Iraq and trained other females on weapons and explosives. Some of the females were threatened with sexual videos they appeared in if they didn’t carry out their orders, which included renting safe houses and buying supplies.

The Merger of Jihad in Iraq and Syria

To understand the significance of these foreign units one must go back to August 2011 when Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi was the leader of the Islamic State of Iraq, an official branch of al-Qaeda. He had no more than several hundred members when he sent a group of his men led by a Syrian man called Abu Mohammed al-Julani to Syria to establish a base, taking advantage of the security vacuum caused by the Syrian revolution. In January 2012, the group was called al-Nusra Front.

Al-Nusra attracted many of the foreign fighters who came to fight with the Free Syrian Army, and it used them in its expansion. By April 2013, Baghdadi became so suspicious of al-Julani’s increasing success and independence that he decided to declare the merger of the Islamic State in Iraq and al-Nusra Front into the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), saying that he had established, funded, and supported al-Nusra.

A power struggle started between the two groups that led to armed clashes. Al-Qaeda chief Ayman al-Zawahiri ruled against al-Baghdadi and finally disavowed his group from al-Qaeda in February 2014.

By that time, ISIS had managed to attract most of the foreign fighters who joined al-Nusra. One of the reasons was that ISIS used that period of time to gradually dominate the city of Raqqah, the only major city in Syria controlled by the rebels. By January 2014, ISIS completely controlled al-Fallujah in Iraq and al-Raqqah in Syria. By controlling cities, it drew foreign fighters to its ranks.

“Aligning with ISIS gives other rebel groups access not only to supplies and weapons, but also to the ISIS brand, therefore raising their status and appeal to individuals looking to join the movement. The cachet the Islamic State lends to groups (both hardened fighters and newcomers), is immense. Once a unit folds into the Islamic State, they can be guaranteed support and success in battle,” said Joe Balzano, one of the four TRAC researchers who conducted the research.

ISIS emerged from Iraq in 2010 with no more than several hundred fighters. But with its Syrian success in 2011 and 2012, and by infiltrating the Iraqi Sunni protests in 2013, it managed to create the momentum to attack Abu Ghraib prison, on the outskirts of Baghdad, in July 2013 and free hundreds of its best commanders and fighters, many of whom were former Iraqi army officers who now make up the majority of Baghdadi’s advisers. Then it used those fighters to dominate al-Raqqah and capture Fallujah in January 2014. ISIS finally launched the June assault in Iraq and captured Mosul, Tikrit, and many other cities and towns. Today, ISIS controls no less than a third of Iraq and a third of Syria, making it the de facto ruler of no less than 6 million people with more lands than any other party engaged in the twin Syrian-Iraqi wars, including the Iraqi and Syrian governments.

ISIS is the de facto ruler of 6 million people, with more land than the Iraqi and Syrian governments.

“The advancement of the Islamic State was a polarizing force that caused many idealists to switch sides from Nusra to Islamic State. The phenomenon of defection and conversion among foreign fighters, to me, is indicative of the larger over-trend that Nusra, and by extension al-Qaeda core, is softening the hard-line attitudes towards the Islamic State,” said Veryan Khan, another TRAC researcher.

November 2013 was a major date in the defection of foreign units from the Free Syrian Army or al-Nusra Front to ISIS. The Chechen and the Egyptian units joined ISIS that month, giving the organization a boost. In March and April 2014, Belgians and Palestinians joined. July 2014 was also a decisive month as ISIS employed its successful June campaign in Iraq and attracted another Libyan unit along with three Syrian units, the research states.

ISIS used the service of those foreign units and their fighters effectively. Every unit was capable of fighting, but some had special capabilities. According to TRAC research, the all-female British unit (it has other nationalities as well) operates like a police force in al-Raqqah and recruits female fighters in al-Anbar in Iraq. The Lebanese unit has a strong online German-language presence, perfect for propaganda and recruiting. The Belgian unit is used to hold western hostages. Former Belgian hostage Dimitry Bontinck says he saw the murdered U.S. hostage James Foley and the current British hostage John Cantlie being held by the Belgian unit before being transferred to ISIS in Aleppo.

One of the German units is not only recruiting fighters in Germany, but Denmark as well. A member of the second German unit was shown beheading Syrian army soldiers in a propaganda video in the Syrian town of Azaz. Other members of that unit blew themselves up in suicide attacks near Mosul in August 2014 and Baghdad in July 2014.

Some members of one of the Dagistani units were involved in the beheading of Father Francois Murad, a Catholic priest, in June 2013 in Syria. The Indonesian unit was used to recruit fighters from Indonesia and Malaysia. The multinational foreign unit is used as the ISIS elite force that attacked the Abu Ghraib prison in July 2013 and Mosul in June 2014.

One of the main ways ISIS foreign fighters are used is as suicide bombers. A list of ISIS suicide attacks in Iraq from June through October was leaked to the Iraqi news website Ynews. The list shows that ISIS conducted 67 suicide attacks in five months. Fifteen of the suicide bombers were Saudis. Eight were Iraqis. Six were Tunisians. Five were Moroccans. Syrians, Libyans, Uzbekistanis, Palestinians Azerbaijanis, Germans, Turks, Lebanese, Indonesians, Australians, Pakistanis—all took their own lives.

A Key Foreign Commander

One of the most prominent and important foreign fighters who joined ISIS is Abu Omar al-Shishani, whose biography is detailed in the TRAC research. Born Tarkhan Batrirashvili in northeast Georgia in 1986, when it was part of the former Soviet Union, he is the son of a Georgian Orthodox father and a Chechen Muslim mother. His village had thousands of Chechen refugees during the 1990s. Some of them were fighters.

Shishani joined the Georgian army intelligence in 2006 and fought during the Russo-Georgian war in 2008 as a sergeant. In 2010, instead of being decorated and promoted to be an officer as he was expecting, he was discharged after being diagnosed with tuberculosis. His mother died of cancer and he couldn’t find a job. At that time, he started his path toward extremism. He was arrested and sentenced to three years for illegal weapons harboring.

He was released after spending less than half of his sentence in prison, but he had become further radicalized by then and left the country immediately after being released. He went to Turkey, then to Egypt, and ended up in Syria in March 2012, where his brother was as well.

Shishani introduced maneuvers that enabled ISIS victories in key battles and changed IS tactics from conventional warfare to agile mobile units and hit and run assaults.”

He joined and commanded a foreign unit called “Muhajireen Brigade,” or the army of immigrants. This unit helped al-Nusra front in several attacks in Aleppo in 2012. Then in March 2013, this unit merged with other two Syrian units to form a larger unit called “Jaish al-Muhajireen wal-Ansar,” or the army of immigrants and helpers. This unit participated in the attack on Menagh air base in August 2013 and the Latakia offensive in the same month.

During that time, al-Shishani started to shift his loyalty to ISIS. By November 2013, his army was divided, with some joining al-Shisani to be part of ISIS and others remaining outside the group. He also managed to attract an Azerbaijani unit to join him as well.

He rose up within ISIS senior leadership councils and he is believed to be ISIS’s most senior military commander in Syria now. “Shishani is credited with introducing battlefield maneuvers, such as feints and encirclement, that enabled IS victories in key battles. Shishani is also seen as the leader that introduced a change in IS tactics from conventional warfare to agile mobile units and hit and run assaults (guerrilla warfare),” the TRAC research said.

Fighting ISIS's Foreign Appeal

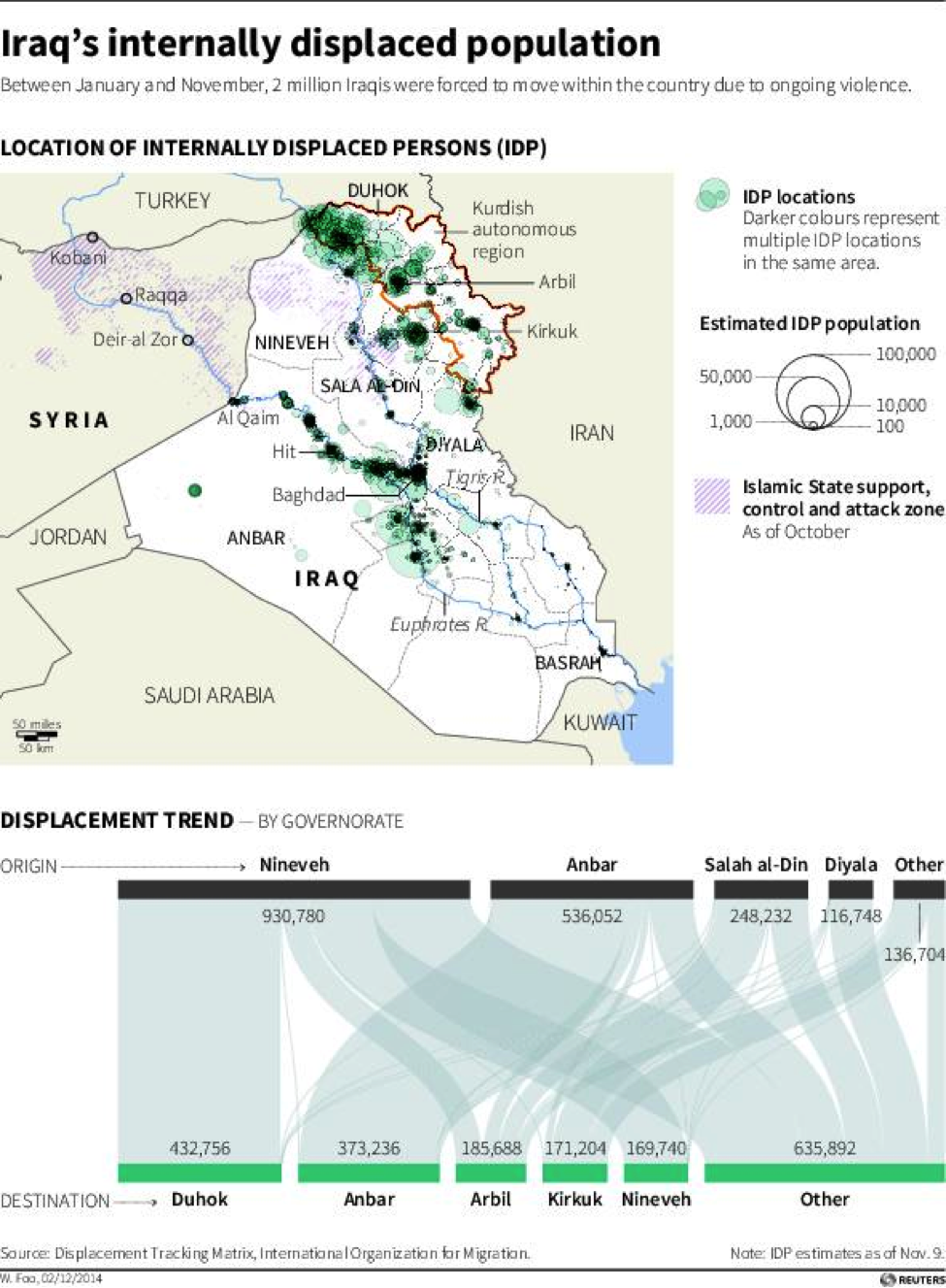

ISIS operates or tries to operate like a state. Its fighters get salaries that range from several hundreds of U.S. dollars to a few thousand. In every city or village ISIS captures, thousands of residents leave their homes to seek safety elsewhere. The refugees now number in the millions in both Iraq and Syria. ISIS confiscates their homes and properties and uses them to house the foreign fighters.

In a video released by ISIS, a Saudi man appears and talks about his job at ISIS where he is assigned to take care of sheep confiscated from the Yazidis in Sinjar. ISIS also uses its oil trade, tax collection, hostage taking, and public funds to supply its fighters with food, clothing, and other equipment. Arms and ammunition have been provided through ISIS victories in Iraq and Syria over the Iraqi security forces, the Syrian army, and Syrian rebels.

After the U.S.-led air campaign against ISIS began in August 2014, a worldwide effort began to counter ISIS’s gigantic recruiting machine. Governments around the world tightened their measures against ISIS recruiting suspects. A similar campaign was launched to remove ISIS Twitter accounts and YouTube videos; 180,000 of them were removed as of early November, estimated Hisham al-Hashimi, a researcher on ISIS.

The ISIS economic empire was targeted too. Its primitive oil industry and trade were targeted by the U.S.-led air bombing and by a crackdown on oil trafficking with Turkey and Kurdistan, where networks of profiteers were arrested. More pressure was aimed at the rich gulf countries to do the same with their citizens who are financing ISIS.

In Iraq, the new government changed the military command and started to fight corruption. A series of victories were achieved in every province against ISIS. Several towns and cities were restored to Iraqi rule. Yet, the big cities like Mosul, Falluja, and Tikrit are still controlled by ISIS. In Syria, the picture is not bright. The Free Syrian Army is still struggling to be a reliable force that can defeat or even fight ISIS.

As a result of all these efforts, Hashimi said, the numbers of foreign fighters crossing to Syria dropped from 50 to 5 a day. Whether the drop can be sustained is yet to be determined.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: