Nearly half of American families have no retirement savings at all, the Economic Policy Institute reported in March.

As the share of Americans aged 65 or over is expected to double by 2060, the country faces a potential retirement crisis, one that’s been driven in large part by the shift from traditional pensions to 401(k)s.

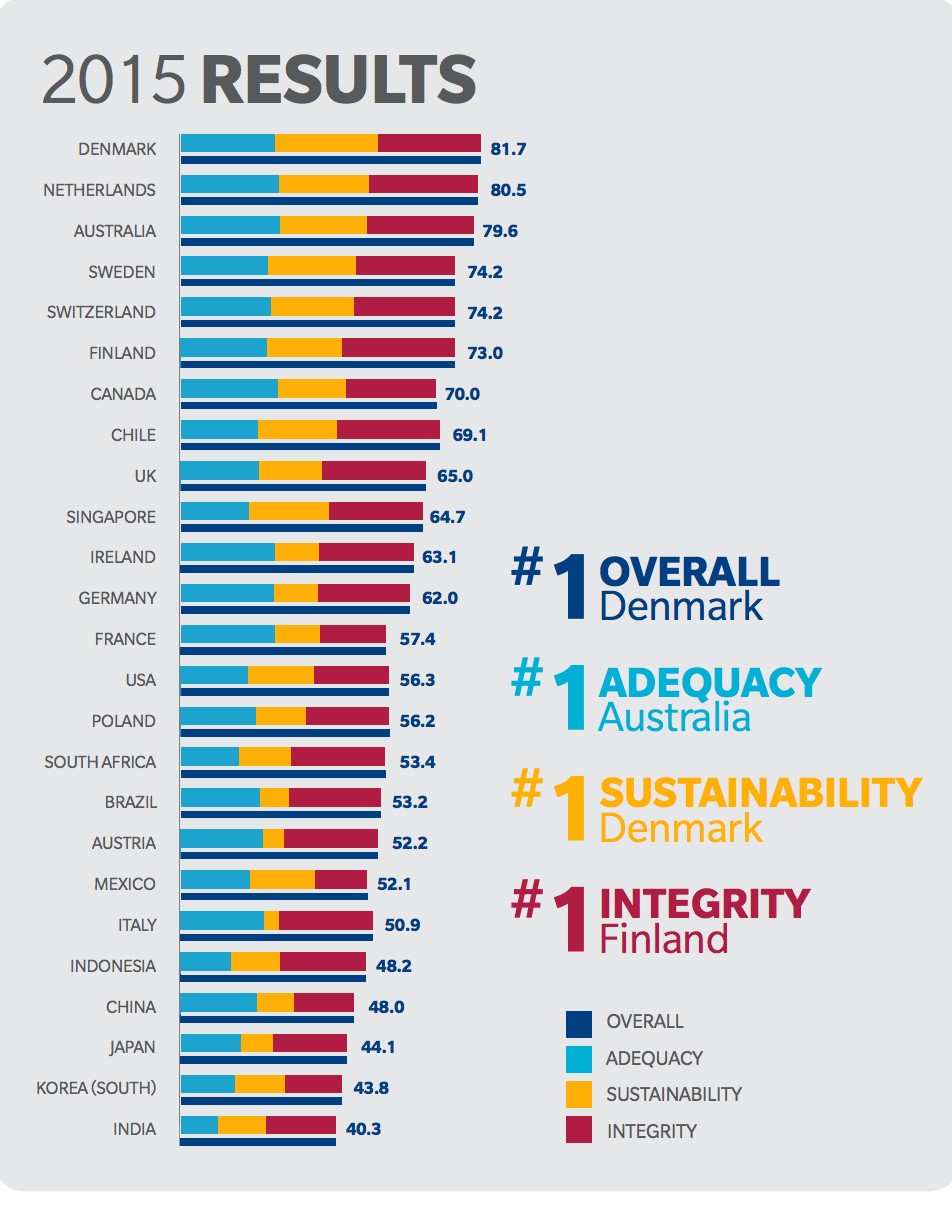

America’s retirement system clearly has room to improve, and that widespread sentiment is backed up by the 2015 Mercer Pension Index, a rating of 25 pension systems around the world. Mercer, a global human resources consulting firm, ranked the U.S. pension system 14th of the 25 countries on the list, with a “C” grade. Mercer rates countries annually based on how adequate the benefits provided are, how likely the benefits will be provided into the future and how well the pension programs are run.

Related: The Retirement Revolution That Failed: Why the 401(k) Isn’t Working

For the U.S., Mercer suggested that making retirement plans mandatory could be one way to strengthen the pension system. Last week, Rep. Joe Crowley (D-NY), vice chair of the Democratic Caucus, introduced legislation meant to address this issue by providing a universal retirement account for every American.

Source: Mercer

The bill would require employers with a staff of more than 10 who don’t currently have a retirement plan to establish a retirement account for every employee, to which they would contribute 50 cents for every hour worked. Three percent of an employee’s pre-tax income would go toward the retirement fund automatically, unless the worker decides to opt out. Smaller employers would be eligible for a tax credit worth the value of contributions to 10 employee accounts.

Crowley’s proposed legislation comes alongside Sen. Jeff Merkley’s American Savings Account Act that would set up a new universal savings account. But if Merkley’s bill is any indication (it hasn’t yet moved since January), the chances of passing the Crowley bill are slim. Still, some states, including Illinois and Oregon, have passed pension auto-enrollment laws.

Related: The Retirement Cost That 80% of Americans Aren’t Ready For

Below are a few other ideas from countries that made Mercer’s top 10 best pension systems. The key question, as always, is how to pay for such programs, though it’s possible that employers could play a bigger role in helping Americans grow their retirement nest eggs, especially if the corporate tax rate is lowered.

1. Denmark: Employers Must Pay Two-Thirds of Employee Pension Plans

(Mercer rank: #1)

In addition to the means-tested Danish state pension (the folkepension), for employees aged 16 to 67, Danish employers must contribute to the occupational pension plan called the ATP, in which the employer pays two-thirds of the pension plan contribution, while the employee is responsible for one-third of the contribution. In addition to the ATP, some employers’ associations participate in voluntary pension programs. (Denmark’s nominal corporate tax rate is 22 percent; the U.S. is 35 percent, not including state taxes.)

Related: 6 Brexit Lessons for Your Retirement Nest Egg

2. Australia: Mandatory Contributions from Employers Increase as Population Ages

(Mercer rank: #3)

Australians have been entitled to a state pension since 1992, and employer contributions have been compulsory for employees aged 17 to 70 making more than $450 Australian dollars ($342) per month. Currently, on top of salary and benefits, employers must contribute 9.5 percent of an employee’s income to pension funds each year, an amount that will increase to 12 percent by 2025. (Australia’s corporate tax rate is 28.5-30 percent.)

3. Singapore’s Central Provident Fund

(Mercer rank: #10)

Singapore has long been recognized as a leader among Asian countries for pensions and social security. The country’s Central Provident Fund, established during British colonial rule in 1955, is responsible for Singaporeans’ retirement funds. The fund has separate accounts for basic needs, health care, housing and insurance programs. The contribution formula depends on the age of the employee. Private sector employees under 55 contribute 17 percent of their wages to the CPF, while employers set aside 20 percent. For employees aged 55 to 60, both employers and employees contribute 13 percent. (Singapore’s corporate tax rate is 17 percent.)