At the end of 2013, when the unemployment rate was still high at 6.7 percent and the country was still struggling to dig out of the economic hole created by the Great Recession, a federal program extending the duration of unemployment insurance expired. With millions of Americans out of work, many for six months or more, Republicans in Congress declined to renew the program.

The benefit that had been available for nearly two years -- 99 weeks -- was slashed to about 26 weeks in some states, leaving an untold number of American families in desperate economic straits. Efforts by the Democratic-controlled Senate to renew the program were filibustered twice by Republicans. In the House, Speaker John Boehner repeatedly declined to allow a vote on renewal knowing that an extension would not pass.

Related: How Reduced Middle Class Wages Are Stagnating the US Economy

At the time, the justification for denying extended benefits was a sort of “tough love” argument. Kentucky Sen. Rand Paul said extending unemployment insurance benefits was “a disservice” to the unemployed because it caused them “to become part of this perpetual unemployed group in our economy.”

James Sherk, a labor economist with the conservative Heritage Foundation, said the extension program “causes people to be more selective,” about what jobs they will accept” and “encourages very counterproductive job search decisions.”

However, a recent study suggests that all that pain inflicted on the unemployed for their own good was largely ineffective.

Related: IMF Warns of Stagnant US, Global Economy

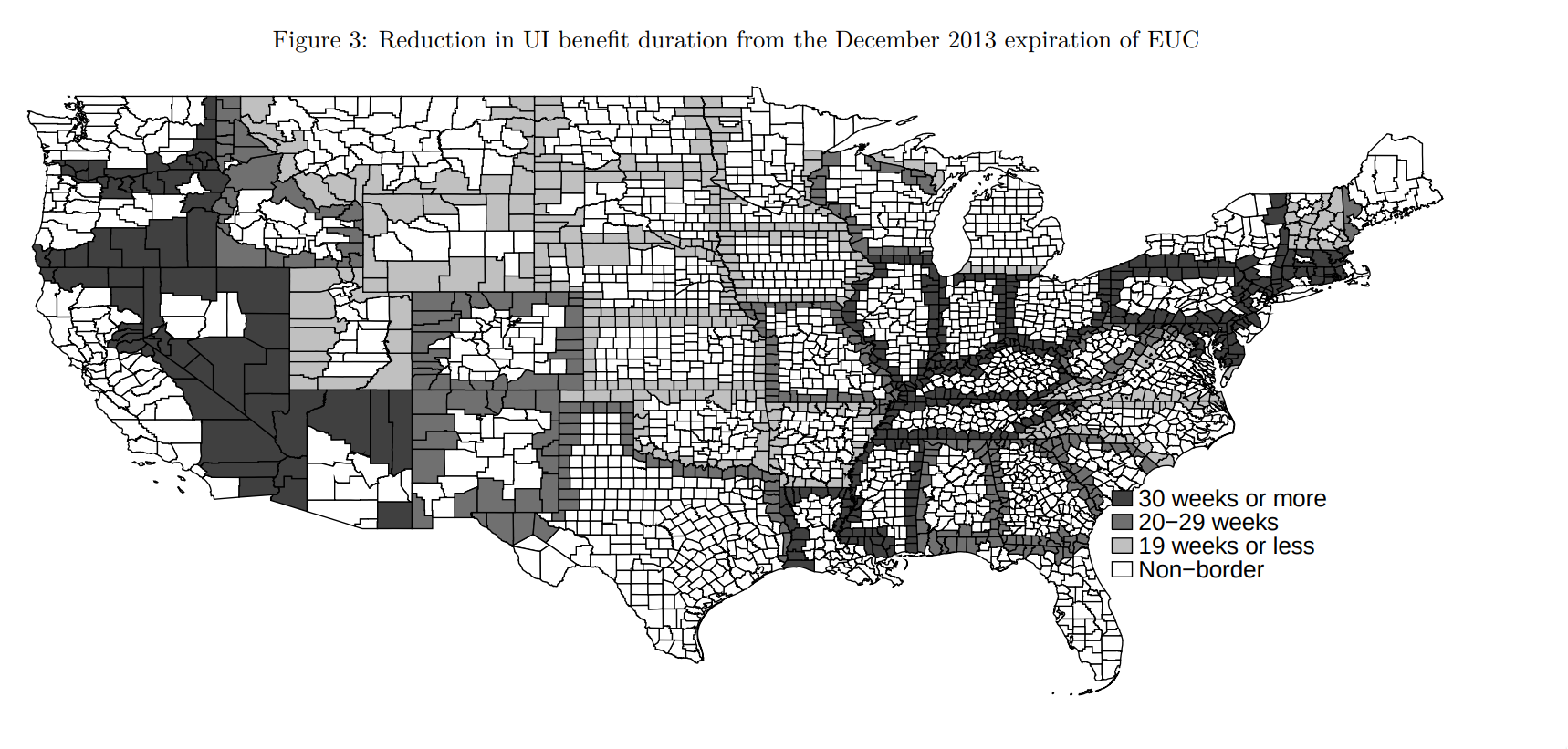

Economists Christopher Boone, of Cornell University, Arindrajit Dube of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, and Lucas Goodman and Ethan Kaplan, both of the University of Maryland, used the natural experiment created by states that implemented their own reductions in unemployment insurance duration to compare the employment impact on border counties across state lines.

What they found is that keeping people on extended unemployment benefits during a crisis has virtually no impact on the percentage of the population that is employed.

“[W]e find no evidence that UI benefit extensions substantially affected county-level employment,” they write. The effects of extending the benefit from 26 weeks to 99 weeks “are not significantly different than zero, and they allow us to rule out negative effects on [employment-to-population ratio] greater than -0.50 percentage points at the 95% confidence level.”

What other research has found, though, is that extra assistance during an economic downturn helps people navigate tough economic times, and taking it away does serious economic and societal harm at the individual and family levels.