A key element of the Republicans’ plan for replacing Obamacare is transforming the costly Medicaid program into a series of block grants to the states. The idea is to save the federal government billions of dollars in the coming years while giving state officials more flexibility to set eligibility requirements and spending levels to provide health care services to the nation’s poor and disabled.

But there is one serious catch: While the extensive use of block grants has proven over the years to be a great financial boon for Congress and the federal government in attempting to rein in spending, it has been a bad deal for the states and hundreds of millions of Americans dependent on federal assistance.

Related: Why the GOP Plan for Medicaid Could Be a Bad Deal for the States

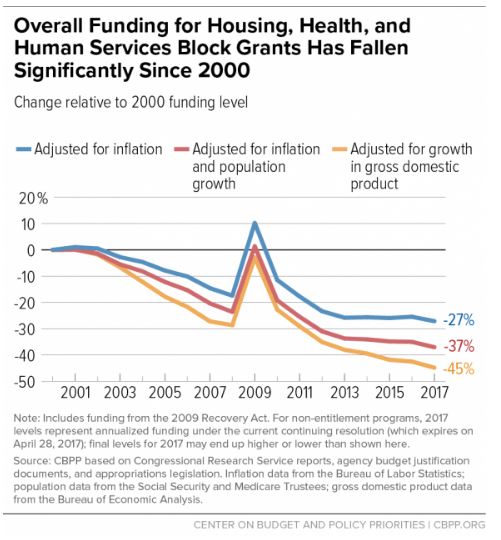

Federal funding for 13 major block grant programs for housing, health, and social services has dropped by 27 percent or $14 billion since 2000 or by 37 percent when adjusting for inflation and population growth, according to a new analysis by the liberal-leaning Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

David Reich, a senior fellow on federal fiscal policy and a co-author of the study, said in an interview Wednesday the simple fact is that “funding for block grants tends to decline over time.”

“If you convert programs to block grants and combine programs into block grants, very likely – based on history – the funding is going to go down – it’s not going to keep pace with need,” he added.

In the distant past, Congress poured tens of billions of dollars into state coffers through categorical grants and formulas that were targeted for specific activities and purposes. But that began to change in the 1980s during the Reagan administration when those funds were bundled into broader spending categories under the rubric of block grants.

Related: How Block Grants Cap Federal Costs -- and Make States the Bad Guys

The original purpose was manifold – to grant the states more authority and flexibility to tailor services to constituents’ needs while looking for ways to make savings to stay within the block grant amounts. Over time, however, Congress and the executive branch viewed the block grant system primarily as a money saver.

Today, block grants range from home investment partnerships and job training to substance abuse prevention and community development action.

The largest block grant in the study -- the 1997 welfare reform program known as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) – currently receives $16.57 billion annually and has lost a third of its value due to inflation. It was designed to encourage more people to work rather than to rely on welfare. At the same time, the amount of basic assistance TANF provides has fallen even more as states shift those resources to other programs.

Low income and impoverished Americans are not left in the lurch, however, since they have access to a variety of other federal safety net programs including food stamps (SNAP), Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), Supplemental Security Income (SSI), Housing Assistance, Child Nutrition Program (CHIP), Feeding Programs (WIC & CSFP), Low-Income Home Energy Assistance, and Lifeline (a free cellphone service).

The Community Development Block Grant totals $2.99 billion annually, down 51 percent from 2000. The $1.85 billion that goes for substance abuse prevention and treatment totals $1.85 billion, down 19 percent from 2000.

The loss of funding for these and other programs is even more pronounced when measured against the relative size of the economy, which has grown substantially since 2000. In 2000, total block-grant funding equaled 0.36 percent of the economy, according to the report. By 2017, this share of GDP had dropped to 0.20 percent, a decline of more than two-fifths. It’s not clear if the community development programs failed to meet performance benchmarks or if the substance abuse and prevention treatment dollars were replaced by grants to existing medical facilities or rehab centers.

Related: Trump Cracks Down on Sanctuary Cities – and It Could Cost Them Billions

Among the 13 programs in the study, only the Child Care and Development Fund and the Community Mental Health Services Block Grant have grown since their inception, in 1997 and 1993, respectively.

“An unfortunate irony here is that while policymakers assert state flexibility as a prime reason to block-grant programs, this flexibility can later be used to justify cutting them or eliminating them entirely,” the report states.

A good example was when Congress created the Social Security Block Grant in 1982 to give the states more administrative and policy flexibility over the services provided. Over time, conservative lawmakers complained that the program was giving the states too much flexibility and that it had turned into a “no-strings-attached” slush fund.

Now conservatives are considering giving states block grants for Medicaid.

The 1965 Medicaid law today covers about 81 million people, including poor children and pregnant women, the disabled and poor older people. Republicans have long complained about runaway spending, fraud and waste. Medicaid spending grew 9.7 percent to $545.1 billion in 2015, or 17 percent of total national expenditures on health, according to the Department of Health and Human Services. That increase was twice the rate of growth in spending for Medicare for the elderly.

Related: What Obamacare Repeal Could Mean for Your Workplace Health Plan

What's more, government spending on Medicaid expansion under Obamacare turned out to be much higher than original projections, according to an analysis by Forbes. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) estimated in its 2014 Medicaid Actuarial Report that newly eligible enrollees would cost $4,281, on average, in 2015. Yet in a 2015 report issued in July 2016, CMS raised the per capita cost to $6,366—a 49 percent increase.

A dramatic upward revision of enrollment and spending for each enrollee significantly altered the bottom line cost for expanded Medicaid, Forbes noted. In April 2014, the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office estimated that the federal share of Medicaid expansion spending would be $42 billion in 2015. The actual federal cost turned out to be roughly $68 billion — or 62 percent higher than predicted.

GOP efforts to convert Medicaid from a federal entitlement covering all eligible people to block grants to the states dates back to the Reagan administration.

As now portrayed by House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-WI), a block grant would essentially cap federal Medicaid funding as a way of achieving major savings in the coming decade. At present, the federal government picks up a fixed percentage of states’ Medicaid costs — on average 57 percent — and the states cover the rest. Under a block grant approach, states would receive a fixed amount based on a formula, with the states responsible for picking up any additional costs above the cap.

Last November, CBPP issued an analysis showing that a block grant proposal included in a House GOP budget plan for fiscal 2017 would cut federal Medicaid funding by $1 trillion — or nearly 25 percent — over ten years, relative to current law. Another analysis by the Urban Institute of a previous block grant proposal promoted by Ryan in 2012 projected that between 14 million and 21 million people would eventually lose their Medicaid coverage.