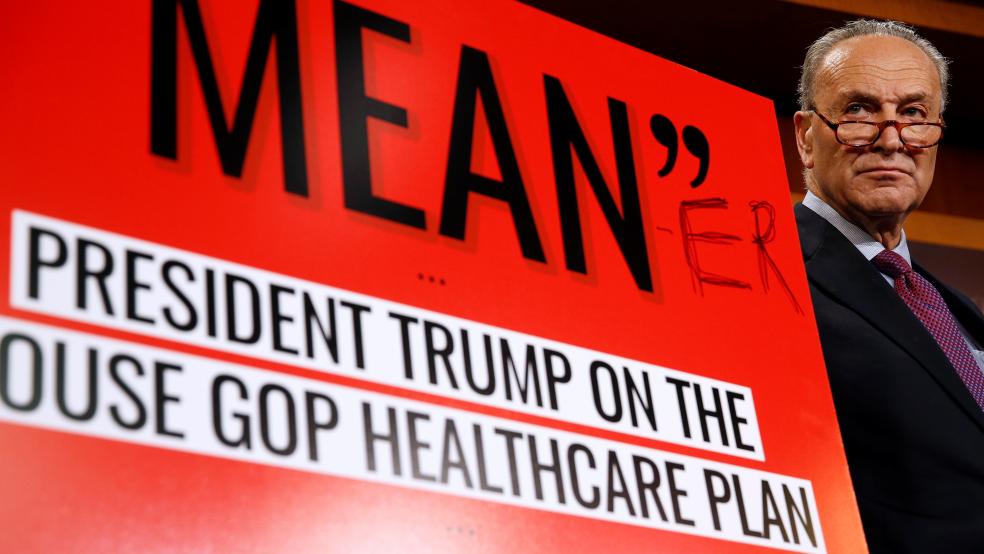

President Trump urged Senate GOP leaders to produce a bill to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act that wasn’t as “mean” as the recent House-passed version. But critics say that, at least in the way the Senate plan treats Medicaid in the coming decade, the Senate version is a lot meaner.

The half-century old Medicaid program provides health care coverage for 74 million low-income, with services ranging from hospitalization, physician and dental care, prescription drugs and pediatrics to skilled nursing home care for the disabled and elderly. Senate Republican aides said that the GOP plan “strengthens Medicaid for those who need it most” by giving states more “flexibility” while ensuring that those who rely on this program “won’t have the rug pulled out from under them.”

Related: Why Some GOP Senators Are Balking at Their New Health Care Plan

But critics in both parties responded with dismay to the long-term blueprint for overhauling Medicaid, which some analysts say could force 14 million or more beneficiaries off the rolls by 2026 and jettison many of the services currently provided.

Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) described the plan released on Thursday by Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) as “a wolf in sheep’s clothing, only this wolf has sharper teeth than the House bill.” Sen. Dean Heller (R-NV), a moderate who is facing a tough reelection campaign next year, said that “At first glance, I have serious concerns about the bill’s impact on the Nevadans who depend on Medicaid.

Robert Greenstein, head of the liberal-leaning Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, said he was “stunned” by the harshness of the Senate GOP plan and would “do more harm” to Medicaid and the rest of the health care system than any other piece of legislation he can recall over the past 45 years.

The bill -- dubbed the Better Care Reconciliation Act -- is similar to the House-passed version. It would cut spending on the Medicaid program for the poor and disabled by more than $800 billion over the coming decade and gradually roll back expanded Medicaid coverage for low-income, able-bodied, childless adults in 31 states and the District of Columbia who were previously ineligible for traditional Medicaid.

Related: Uncertainty Over Obamacare Drives Up Average Premiums 18% Next Year

However, the legislation is surprisingly tougher on Medicaid than the bill that narrowly emerged from the House in early May, especially in curbing the long-term growth of federal funding for the program.

McConnell, who drafted the legislation behind closed doors with the help of a few trusted aides, indicated on Thursday that the bill is still a work in progress. However, the proposals for overhauling Medicaid are encountering strong resistance from a handful of moderate Republicans, including Sens. Rob Portman of Ohio, Susan Collins of Maine, Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, Shelley Moore Capito of West Virginia and Heller.

Here are five reasons these moderates and others aren’t happy with the plan:

Phasing out expanded Medicaid: Under traditional Medicaid, the federal government and states share in the cost of coverage, with the feds picking up as much as 60 percent of the cost and the states picking up the rest – and with no limit on overall spending.

Related: Here Are Six Key Differences Between the House and Senate Health Care Plans

The expanded Medicaid program under Obamacare has been a major boon to the states that chose to participate because the federal government at first assumed all the cost of the expanded coverage and currently is picking up 95 percent of the cost. Unlike the House-passed bill that would freeze and phase out the program in 2020, the Senate approach would begin ratcheting down federal funding in 2021 and would completely eliminate the bonus funding by 2024.

At that point, states would receive the same federal match rate as they currently do under traditional Medicaid. But some moderates, including Portman and Murkowski whose states benefit from expanded Medicaid, have called for a longer phase-out period of seven years, to assure a “smooth glide path.”

Deep cuts in the overall Medicaid program: It won’t be clear until the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) analyzes the bill, but the Senate version is almost certain to cut $834 billion or more from Medicaid over the coming decade, as does the House-passed plan. These cuts will be essential to offset revenue losses that will be incurred when Congress repeals a host of taxes that were imposed to finance the Affordable Care Act.

Related: New White House Website Undermines Affordable Care Act

Those savings would be achieved in a number of ways, but primarily by changing the way the federal government and states share in the cost of Medicaid. That would be done by adopting a new per-capita-cap system that would limit future federal contributions to a set amount per beneficiary and gradually shift more of the financial responsibility to the states.

Stingy cost-of-living adjustment: The Senate and House versions of the bill significantly differ on the rate at which the federal government would provide per capita support for Medicaid beneficiaries, with the Senate approach surprisingly stingier than the House. The Senate bill would link increases in funding for Medicaid to the Medical Consumer Price Index plus 1 percentage point through 2025. But then it would switch to the urban Consumer Price Index.

The CPI-U, as it is known, is substantially lower than the projected rate of medical inflation, and even further beneath the projected Medicaid growth rate. Health policy experts have warned that such a sharp reduction in Medicaid funding would leave individual states facing the prospect of either reducing services or increasing their own spending on Medicaid.

Related: How the Opioid Crisis Could Derail the GOP Health Plan

Greenstein says the compounding effect of a lower cost-of-living adjustment will accelerate in the coming decades and put many states deeper and deeper in the hole.

At least 14 million would be dropped from the rolls: The CBO has estimated that at least 14 million Americans will lose their Medicaid coverage by 2026 under the House-passed version of the Obamacare repeal and replace legislation.

Although we must wait for the CBO to complete its analysis of the Senate GOP version, some experts say that CBO is likely to conclude that a similar number would be dropped from Medicaid under the Senate plan.

Related: Obamacare Repeal Could Be a Big Setback for the Fight Against Addiction

Extra money for drug addiction treatment: Moderate Republicans from states tragically swept up in the opioid epidemic – including Sens. Portman and Capito -- are worried that the cuts in Medicaid spending would torpedo desperately needed coverage for drug addiction and mental health treatment.

Portman and Capito demanded that McConnell includes in the legislation $4.5 billion a year for the next ten years for drug addiction treatment, but the bill as unveiled would provide only $2 billion in fiscal 2018. Portman warned that he would oppose the health care legislation unless there is far more Medicaid funding of drug treatment.