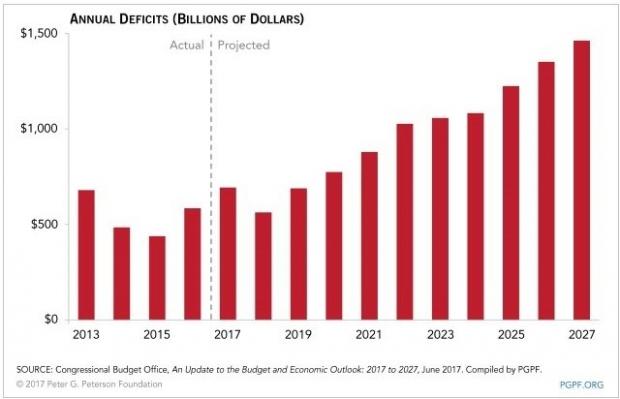

While the Trump administration and a Republican Congress press for a major military buildup, new infrastructure and trillions of dollars’ worth of tax cuts, the federal government has quietly begun inching its way back to an era of historic budget deficits of $1 trillion or more a year, according to the Congressional Budget Office’s latest budget and economic outlook.

The non-partisan agency issued an updated report on Thursday projecting a $693 billion deficit for fiscal 2017, or $134 billion above a previous projection and the highest since 2012. But absent any significant change in government policy -- especially as it relates to steadily rising Social Security and Medicare costs for the elderly -- deficits will grow dramatically over the coming decade.

Related: The Five Biggest Winners and Losers in Trump’s Fiscal 2018 Budget

Annual revenue shortfalls of $1 trillion or more once dominated the headlines and the debate on Capitol Hill, but for now seem like a dim memory.

President Obama inherited the worst recession of modern times upon entering office in January 2009 and presided over massive budget deficits that went as high as $1.4 trillion over four consecutive years before reversing, bottoming at $396.5 billion in fiscal 2015 as the economy recovered.

After an extended lull in the flow of government red ink, the deficit began to grow again last year and now appears on a trajectory to return to levels of between $1 trillion and $1.5 trillion a year between 2022 and 2027.

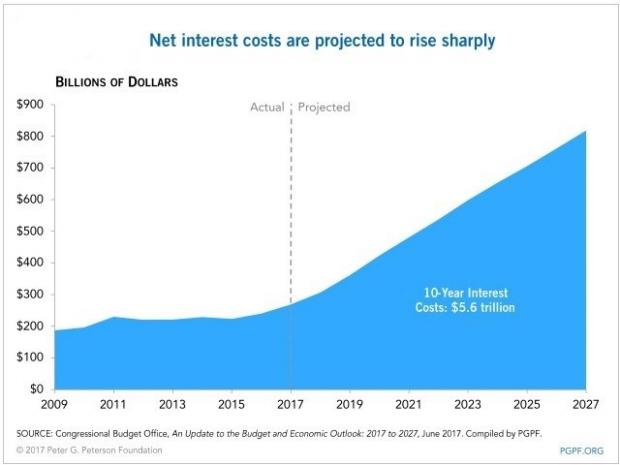

Robert L. Bixby, executive director of the Concord Coalition, an anti-deficit group, said he is troubled by the new report, especially the government’s rising interest costs and a new wave of trillion-dollar-a-year deficits now looming on the horizon.

Spending is expected to grow by $2.6 trillion between 2017 and 2027, and 83 percent of those total expenditures will be for Social Security, health care and interest on the U.S. debt.

Related: The Navy’s New Carrier Is Billions Over Budget – and the Next One Will Be Too

“What bothers me is that the numbers not only look worse, but it’s a very steep increase in the deficit,” Bixby said in an interview on Friday. “That and the fact that there are no plans even being considered to do anything about it. It’s not like anybody on Capitol Hill or in the White House seem alarmed about this and are trying to do something about it.”

Indeed, prominent Republicans -- ranging from President Trump and White House Budget Director Mick Mulvaney to House Speaker Paul Ryan of Wisconsin and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky -- have promised deficit reduction even while pursuing budget and fiscal policies that will almost certainly add to the deficit if approved.

Trump has proposed a $54 billion increase in defense spending next year, for a total of more than $600 billion – an increase will require Congress to breach a spending cap imposed by the 2011 Budget Control Act to address the long-term deficit. Some House and Senate Republican defense hawks want to spend even more next year, although it’s not clear where all that additional money would come from.

Meanwhile, Trump has proposed a massive tax cut for businesses and individuals that potentially could add between $3 trillion and $7 trillion to the long-term deficit, according to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, unless somehow offset by other savings. Trump and Ryan say the tax cut will practically pay for itself by spurring economic growth and generating more in tax revenues, but few independent economists share in the administration’s supply-side optimism.

Related: Trump’s Budget Cuts to the Social Safety Net Are Greater Than Reagan’s

Finally, House and Senate Republicans are touting their plans to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act that include major reforms of Medicaid, a costly entitlement program for low-income and disabled people. Both plans would sharply reduce spending over the coming decade by nearly $800 billion and would transform the program from a federal entitlement to a per-capita-cap or block grant to the states with fixed payments and a stingy cost-of-living formula.

But instead of devoting those savings to long-term deficit reductions, the Republicans intend to use the Medicaid savings to help offset nearly $1 trillion of tax cuts for wealthy Americans and investors, the health care and pharmaceutical industry, indoor tanning salons and others.

“If you’re going to make a lot of savings in Medicaid and then give them all away in tax breaks, you’re really just shifting priorities,” Bixby said. “You’re not doing anything to address the long-term fiscal outlook.”

The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget said that the CBO projections should “serve as a warning shot” to politicians who want to increase the debt through tax reform or other initiatives. “Rather than add to the debt, we need lawmakers to come together to enact the significant entitlement reforms, spending cuts, and revenue increases necessary to put debt on a sustainable path,” according to the government spending watchdog.

The national debt – the accumulation of annual deficits – will surge significantly over the coming decade, reaching 91 percent of the overall economy in 2027, or more than twice the 50-year historical average, according to the CBO. As a share of gross domestic product, the debt likely will rise from a post-World War II era high of 77 percent in 2017 to 91 percent by 2027.

Related: Defense Expects a Huge Increase, but They May Already Have What They Need

The deficit problem is being fueled by a mismatch between rapid growth in spending for federal retirement and health care programs and rising interest costs on the one hand and moderate growth in revenue collections on the other. Those lagging tax revenues partially explain why the Treasury is heading towards a possible default on its borrowing in mid-October unless Congress agrees to raise the debt ceiling.

CBO and other budget analysts say the growing disparity between federal expenditures and revenues is not sustainable and will require dramatic policy shifts in the coming years.

Government spending will increase from 20.9 percent of GDP in 2016 to 23.6 percent in 2027, while revenues will rise from 17.8 percent of the economy in 2016 to 18.4 percent by 2027.

The 5.2 percentage point difference between spending and revenues defines the budget shortfall.

The latest update report echoes CBO’s previous warnings that Congress is headed towards a day of budgetary reckoning – one that may lead to runaway interest costs, a decline in economic productivity, depleted savings and a loss of flexibility in using tax and spending policies to respond to emergencies or unexpected challenges.

“The likelihood of a fiscal crisis in the United States would increase,” the report stated. “There would be a greater risk that investors would become unwilling to finance the government’s borrowing unless they were compensated with very high interest rates. If that happened, interest rates on federal debt would rise suddenly and sharply.”