President Obama is in luck. After three years of refusing to engage with the business community, the president remains clueless or indifferent as to how we can create jobs. Happily for him, a new study by Harvard Business School professors Michael Porter and Jan Rivkin offers insights into the reasons employers continue to ship jobs outside the country, and what our policy makers might do to reverse the trend.

Obama is not the only politician who might benefit from this work. Earlier this week, Rick Santorum declared, “I don’t care what the unemployment rate’s going to be.” That sentiment should disqualify Mr. Santorum and anyone who shares it from occupying the Oval Office. Today’s unemployment rate of 8.3 percent is unacceptable, and should be the focus of national policy going forward.

This country cannot fulfill its promises to our young people or to the millions on the cusp of retirement unless we can provide high-level jobs for Americans of all stripes. This is the consuming issue of our time –and it is not solely the result of the financial crisis. Rather, according to the HBS study, it is an issue born of a long-term decline in American competitiveness – a decline that may yet be remedied by an aggressive push by both the private sector and the government.

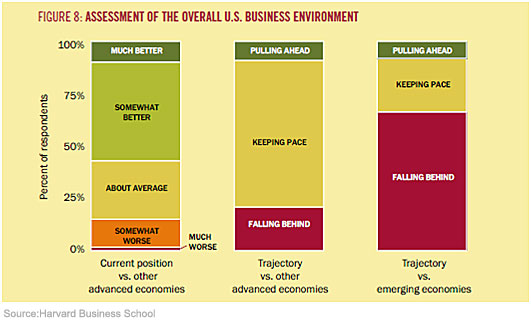

Porter and Rivkin report feedback from an unprecedented 10,000 business types from around the world – more than a quarter of who are in top management slots – about U.S. competitiveness. They asked these alums how they decided where to invest, what were the attractions (or otherwise) of doing business in the U.S., and which sectors were most at risk. Most of those who participated operate globally, and hailed from 122 countries. Bottom line? Over 70 percent of respondents expect U.S. competitiveness to decline in the next three years.

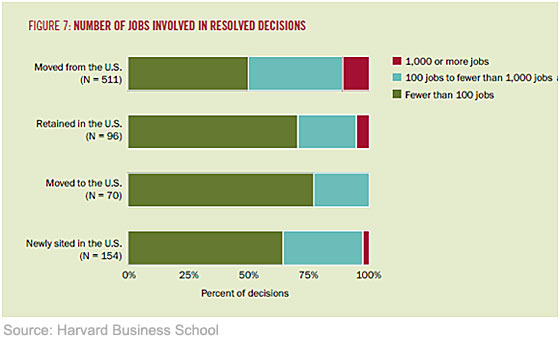

Most important, the survey scrutinized why businesses decide to invest in one country over another. This was not some theoretical exercise. Almost half of the respondents reported that their firm had recently relocated some activity; unhappily, in cases where the U.S. stood to lose operations, it did so 84 percent of the time. Worse, the preponderance of those decisions entailed large numbers of workers – not just in manufacturing but also in high- skills areas like R&D. Where did these jobs go? Not surprisingly, to China, India, Brazil and Mexico – and an additional 146 countries including Togo and Tuvalo. Business knows no boundaries.

The authors break new ground in asking this far-flung executive pool “what are the greatest impediments to investing and creating jobs in the U.S.?” The answer: regulations – and in particular uncertainty about regulations, talent issues, taxes (uncertainty again being cited), macroeconomics and politics.

Porter and Rivkin finally asked each respondent to put forward one concrete suggestion to improve U.S. competitiveness. The top proposal was to simplify the tax code, followed by reforming the immigration process and lowering corporate taxes. Other popular suggestions were improving K-12 education, reforming regulations and balancing the federal budget.

These are the issues that our political leaders should jump on with both feet. The study’s authors note that many of our microelements – entrepreneurship, property rights, management quality, for instance -- are considered strong and enduring. This is the opposite of many developing countries, which struggle to achieve those capabilities, but that have organized the macroeconomic climate to attract investment. We have done the opposite.

Concerns over cumbersome regulations, complex taxes and dysfunctional immigration have boiled up in our nation’s discourse, but unfortunately remain stymied by political wrangling. Take the JOBS Act, which is even now being debated in Congress. This bill, officially the Jumpstart Our Business Start-ups Act, which sailed through the House (390-23) and has been endorsed by the president, has bogged down in the Senate. It offers modest regulatory reforms intended to help small companies – those with less than $1 billion in revenues. These firms are arguably the most burdened by the heavy-handed requirements of Sarbanes-Oxley and Dodd-Frank.

Notwithstanding bipartisan enthusiasm for the bill, Democrats in the Senate have decided that even a slight relaxing of the regulatory noose threatens wholesale misbehavior in the corporate suite. In this opposition they are joined (unaccountably) by the AFL-CIO, consumer protection advocates and regulators like the SEC who might find their turf diminished. The New York Times is aghast that any of the inroads made to hobble our corporations through the vast reaches of recent regulation might be abandoned. Never mind that most of the modern-day scandals of note (think Bernie Madoff) have occurred under the noses of regulators.

Similarly, while tax reform has become one of the buttons that politicians routinely push, few have confronted the tough choices necessary to unwinding decades of generally counterproductive tax loopholes. Democrats talk tax reform as a way of raising revenues while Republicans buy into “reforms” that can be counted on to lower tax receipts. President Obama’s commitment to tax reform goes no further than populist promises to remove various incentives for oil and gas companies and the suppliers of corporate jets. Not exactly visionary.

The business community has tried to make its voice heard in the White House, without much luck. The swift departure of Chief of Staff Bill Daley pretty much ended the president’s outreach to corporate corridors. For community activist Barack Obama, our corporate leaders comprise just another ‘special interest” group. What the president has failed to comprehend is that this interest group is special indeed – it drives the employment bus in our country. Alarmingly, that bus continues to cruise in the slow lane.