The post-election Trump rally has looked unstoppable, even in the face of a Federal Reserve interest rate hike, but that could soon change as the consequences of volatile moves in other assets classes — currencies, commodities, and bonds — take their toll on the economy.

To simplify just a bit, investors need to worry about two main things heading into 2017: The risk of disinflation and the surging strength of the U.S. dollar.

The rise in the dollar was the single largest market response to the Fed's decision last week to raise interest rates for the first time since last December. In addition, policymakers updated their economic projections to include three quarter-point rate hikes next year vs. the two quarter-point hikes they were looking for back in September.

Related: How the Fed’s Hawkishness Puts the Trump Rally at Risk

The U.S. dollar index increased 1.3 percent for the week, rising further out of its two-year trading range to return to levels not seen since late 2002. This is greatly increasing the pressure on emerging market economies, many of which had grown reliant on cheap dollar-based funding as the Fed maintained a weak-dollar/zero-rate regime between 2008 and 2014. That's because as the dollar strengthens against their local currencies, such as the Chinese yuan, the foreign exchange losses directly add to the cost of repaying those dollar-based debts.

The scale of the problem is mind numbing: According to the Bank for International Settlements, dollar credit to non-banks outside the United States reached nearly $10 trillion in the summer of 2015. Of this, $3.3 trillion was from borrowers in emerging market economies. BIS economist Robert Neil McCauley warned at the end of last year that this debt pile leaves "borrowers vulnerable to rising dollar yields and dollar appreciation" — both of which have accelerated in the weeks since Election Day.

The chart above illustrates the extreme growth in this dollar-denominated debt, which has increasingly connected U.S. monetary policy and exchange rate movements with the financial markets of emerging market economies. Witness the fact trading was halted in China's bond market overnight last Thursday as traders responded to Wednesday’s rate hike decision.

Related: What It Will Take for Stocks to Keep Climbing

As interest rates drift higher and the dollar continues to climb as the result of expectations of further Fed hikes and optimism over possible fiscal stimulus measures from the incoming Trump administration, the risk of rising defaults and market turbulence overseas will continue to grow.

American stocks will not be able to ignore this. Not only do many large-cap stocks generate a sizable percentage of their revenue from overseas, the rising dollar will also pressure the value of foreign earnings when repatriated back into the United States. Remember, a stronger dollar was one of the reasons corporate earnings were on the slide for much of the last two years.

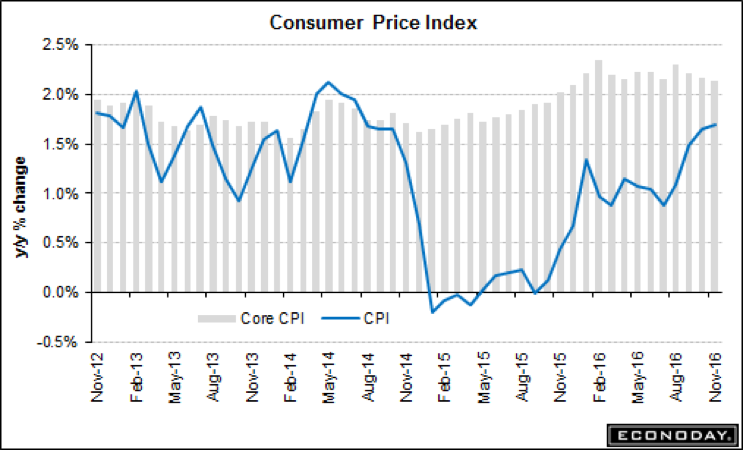

The risk of deflation, or falling prices, may seem odd given evidence of building wage pressure, higher shelter costs and an upward drift in most measures of inflation. As shown above, the headline consumer price index continues to drift higher toward the Fed's 2 percent target. Yet if one removes the impact of higher housing costs — strength in which could be upended by the recent rise in mortgage rates — the overall inflation rate is only just above 1 percent.

Related: How Trump's Economy Can Go Right (or Wrong)

Gluskin Sheff economist David Rosenberg worries that after a final upward spurt of inflation at the start of the year as energy prices eclipse last year's early lows, prices will cool and usher in the return of the disinflation trade along with lower economic growth expectations.

He notes that while post-election confidence could hardly be higher — for consumers, investors and small businesses — actual spending plans haven't really changed. Auto sales were tepid in November. The University of Michigan's consumer sentiment index for December showed declines for spending intensions on both autos and homes. And the NFIB small business sentiment index shows fewer companies intend to boost capital spending in the next three to six months.

It's like everyone is caught up in the whirlwind of eager anticipation but not enough to actually open their wallets. That doesn’t bode well as the market tries to surge to fresh highs.