What happens if Congress fails to raise the debt limit? A new report from the Bipartisan Policy Center examines that question in detail, and the results aren’t pretty. Here are some highlights — or lowlights — from the BPC analysis (the full report is here):

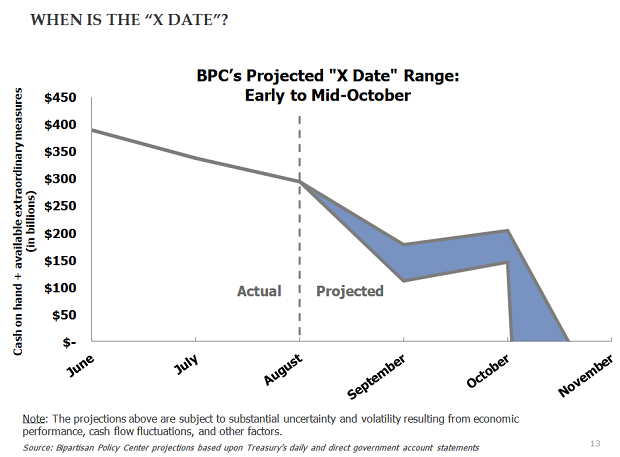

- The “X Date” would come quickly. In a matter of days, the Treasury would be unable to pay all of its bills on time, and would begin a process of prioritizing or delaying payments. The exact date on which the government would start running out of money — the “X Date,” which may be as ominous as it sounds — is not known. But BPC estimates that payment problems would occur in early to mid-October.

- A 23 percent shortfall. Once the Treasury runs out of cash, it would be unable to pay about 23 percent of all obligations in the following weeks.

- October 2 looms large. The government owes about $80 billion to the Military Retirement Trust Fund on that date. Other payments scheduled for October 2 – including Social Security, veterans, civil servant retirement and interest -- total roughly $68 billion.

- The cash deficit would fluctuate. On some days revenues coming into the Treasury would exceed required payments. As a result, the cash deficit would go up and down. But it would tend to rise over time. By October 31, the cash shortfall would stand at about $73 billion.

- The Treasury may prioritize payments. Debt and interest payments may get top priority, to limit the damage in the financial markets. After those payments have been made, the Treasury would choose from the millions of payments that go out each month, selecting some for payment and others for non-payment. Most analysts think this arrangement is technically feasible, but it has never been tested before and involves a host of legal questions.

- Alternatively, the Treasury may start delaying payments. In this second scenario, the Treasury continues to make its scheduled payments, but does so after they due, once enough cash flows in. The delays would grow over time, from days to weeks to months. According to BPC, the Treasury was leaning toward this scenario during the last brush with a debt ceiling crisis, under President Obama.

- Debt downgrades are a distinct possibility. S&P downgraded the U.S. credit rating after a debt showdown in 2011, and Fitch Ratings warned about the status of U.S. debt on Wednesday. Lower debt ratings could mean higher costs to run the government in the future.

While many analysts still think Republicans will find a way to avoid this mess — possibly through a combination of debt limit suspension and a continuing resolution to keep the government running — keep in mind that the markets are showing signs of worry. In late July, the interest rate on 3-month Treasury bills rose above the 6-month rate, a rare inversion that signals serious concern about government finances in the near future. Shai Akabas, economic policy director at BPC, said: “This is a clear signal that investors are worried policymakers will not raise the debt limit in time.”