The middlemen who buy and sell prescription drugs throughout the U.S. healthcare system are inflating prices for consumers, according to an interim report released Tuesday by the Federal Trade Commission.

The FTC says that increasing concentration in the healthcare industry has allowed pharmacy benefit managers, or PBMs, to push drug prices higher, creating billions of dollars in profits for the massive healthcare firms that own them.

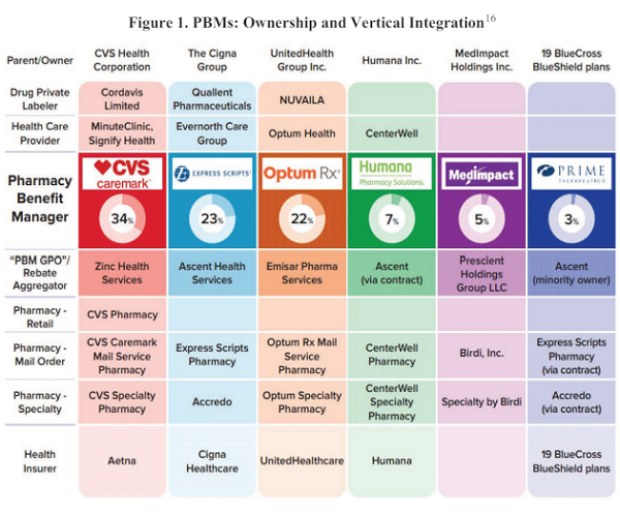

“PBMs are part of complex vertically integrated health care conglomerates, and the PBM industry is highly concentrated,” the FTC says, adding that “this concentration and integration gives them significant power over the pharmaceutical supply chain.” (See the chart below.)

The three largest PBMs – CVS Caremark, Express Scripts and Optum Rx – processed 79% of the roughly 6.6 billion prescriptions written in the U.S. in 2023, while the top six PBMs processed more than 90%.

As a result of this market concentration, PBMs now have an enormous influence over what drugs are available to Americans, and at what prices. “PBMs oversee these critical decisions about access to and affordability of life-saving medications, without transparency or accountability to the public,” the report says.

In some cases, PBMs appear to direct business to the pharmacies they are affiliated with, disadvantaging independently owned pharmacies. And they appear to inflate drug prices through the use of rebate programs that make generic drugs less attractive. “Evidence suggests that PBMs and brand pharmaceutical manufacturers sometimes enter agreements to exclude lower-cost competitor drugs from the PBM’s formulary in exchange for increased rebates from manufacturers,” the report says.

The FTC says the pricing power of PBMs has dire consequences for patients who need prescription drugs, including those being treated for cancer. In one example cited by the FTC, a drug used to treat leukemia, imatinib mesylate, cost almost 250 times more through a PBM than it did through a “non-preferred” pharmacy, as noted by a consultant worried about the “optics” of such a pricing discrepancy.

“[Y]ou can get the drug at a non-preferred pharmacy (Costco) for $97, at Walgreens (preferred) for $9000, and at preferred home delivery for $19,200,” the consultant wrote. “Compounding the challenge/optics is the fact that we’ve created plan designs to aggressively steer customers to home delivery where the drug cost is ~200 times higher. The optics are not good and must be addressed.”

Despite the evidence laid out in the FTC report, the industry denies the findings and blamed drugmakers for the upward trajectory of prices. “These biased conclusions will do nothing to address the rising prices of prescription medications driven by the pharmaceutical industry,” Justine Sessions, a spokesperson for Express Scripts, told The New York Times.

In a statement, FTC Chair Lina M. Khan said her agency would continue to gather information about how PBMs operate, despite a lack of cooperation from the industry. “The FTC’s interim report lays out how dominant pharmacy benefit managers can hike the cost of drugs—including overcharging patients for cancer drugs,” she said. “The FTC will continue to use all our tools and authorities to scrutinize dominant players across healthcare markets and ensure that Americans can access affordable healthcare.”