Wondering whether to jump back into the market after the Federal Reserve’s plan to pump $600 billion into the economy sent stocks to their highest level since September 2008, but worried about the uncertain outlook? People looking for good financial advice can have a hard time.

There are no federal rules for the training or conduct of someone who hangs a shingle as a financial planner. “Certified” financial service providers include more than 100 professional designations, with acronyms like CFP, CFM, CIMA, CFA, CLU, CPA, EA and PFC, representing everything from a single self-study course to years of education, professional training, continuing education, testing and ethics.

Adela Pena, 63, thought she was being responsible when she took early retirement from a telecommunications company in 1998 and invested a $400,000 lump sum pension payment in an annuity recommended by a financial adviser. She watched the value of her portfolio plummet and the adviser stopped returning phone calls. By 2008, she had only $49,000 left.

“Now all I’m living off is my Social Security and the generosity of my children,” she said in an interview from her San Jose, Calif., home. “It’s not like I spend my money foolishly. My children and I never really went on vacation because I wanted to make sure I had some money in my old age so they wouldn’t have to worry about me.”

New Government Oversight

Now, for the first time, financial planners could be subject to government oversight and broker-dealers could be required to act in their customers’ best interests, after two landmark reviews ordered by Congress in this summer's financial regulatory overhaul. The initiatives could reshape the marketplace for financial and investment advice. Policymakers hope new rules will restore some of the confidence shaken by the global financial crisis and stock market collapse in 2008, and better protect investors for the future.

“If I go to someone who markets himself as a doctor or a lawyer, I know that person has passed an exam and that person is subject to a code of professional conduct,” said Marilyn Mohrman-Gillis, managing director for public policy at the Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards, the organization that grants the CFP designation. “It’s easier to be a financial planner than it is to be a cosmetologist.”

In coming months, the Securities and Exchange Commission is set to release a study of whether broker-dealers should have a fiduciary duty to their clients when they give personalized investment advice, and the Government Accountability Office will report to Congress on any new legislation needed to oversee financial planners and protect investors. At the least, reform advocates say, professionals who give individual investment advice should be motivated by the customer’s needs and not the sales commissions they may receive. Currently, brokerages only must ensure that recommended investments are suitable for the investor in question, a lower standard.

Opponents of new standards argue that broker-dealers and insurance agents are already heavily regulated and would pass on to consumers the cost of additional paperwork and compliance.

“The concern is, what impact does that have on small investors’ access to advice and what restrictions on choice will that have?” said Dale E. Brown, president and CEO of the Financial Services Institute. “All that results is an increased cost of doing business, which can inevitably result in advisers no longer being able to service smaller individual accounts.”

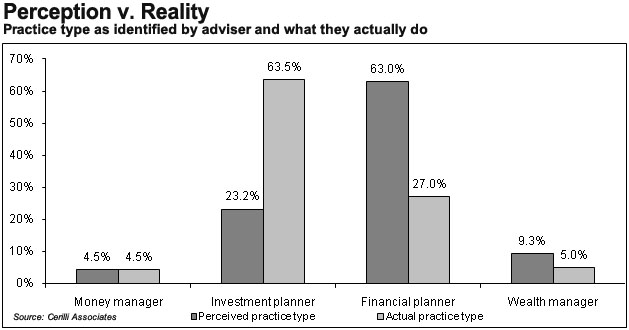

Of 220,000 U.S. financial professionals who call themselves financial planners, only 94,000 are actually delivering “comprehensive” services that include income-tax and insurance planning, with the rest merely providing investment advice, according to an analysis by Cerulli Associates, a Boston-based research firm. A survey by the Partnership for Retirement Education and Planning found that service providers who call themselves financial planners manage three times more total assets and make 40 percent more in gross revenue than others with similar experience level and client mix.

Marc B. Schindler, owner of Pivot Point Advisors in Bellaire, Texas, remembers working as a stockbroker alongside colleagues competing to put clients’ money into the newest mutual fund that the firm wanted to push, regardless of whether it was the best choice for an investor. “Every day I’d have zero on this list and all the other brokers would have hundreds of thousands if not millions by their names,” said Schindler, who left that job to form his own fee-only firm. “I don’t want there to be any commissions or conflicts of interest.”

Some changes are likely, based on Congress’ mandate to consider new rules and SEC Chairman Mary L. Schapiro’s public support. “At the completion of this study, we will have the authority to write rules that would create a uniform standard of conduct for professionals who provide personalized investment advice to retail customers.” Schapiro said in a July speech at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. “I have advocated such a uniform fiduciary standard and I am pleased the legislation provides us with the rulemaking authority necessary to implement it.”

The GAO study could form the basis for legislation to create a standard for the education, training and ethics requirements of professionals who call themselves financial planners. The GAO will report to the Senate Banking Committee, the Senate Special Committee on Aging and the House Financial Services Committee. The financial planning industry itself is calling for oversight, so even a pro-business Congress may not oppose these measures.

A survey by the National Association of Personal Financial Advisors and other financial groups found that 97 percent of investors agree they should receive investment advice from someone who is putting their interests first. “We need to bring reality in line with perception,” said Diahann Lassus, a financial planner in New Providence, N.J., and former NAPFA chair. “Investors do not understand the difference between brokers, investment advisers and financial planners.”

Adele Fagan, a 53-year-old retiree, sees a lot of confusion among her friends in Orefield, Pa., around how to manage money. “People invest in things that are marketed well,” Fagan said. “Very few senior people really understand a lot in the market.”