When it comes to trying to fix the nation’s long term debt problems, there are vast differences over how best to proceed: Just how large should government be? What services should be provided by the government and which should be delegated to the private sector? How much should the government be collecting in taxes to pay for social services? And how deeply should the government cut to help bring the $1.5 trillion annual budget deficit under control?

The answers vary greatly across the political and philosophical landscape. As representatives of six groups that span the ideological spectrum offered prescriptions for dealing with the debt Wednesday at a fiscal summit , Stuart Butler of the conservative Heritage Foundation pointed to one area of agreement in their competing proposals: the importance of preserving a safety net for vulnerable citizens.“There can be agreement,” Butler said, “that it's very important to make sure that there is real security for people who are poor and for people who suddenly come into some problem.”

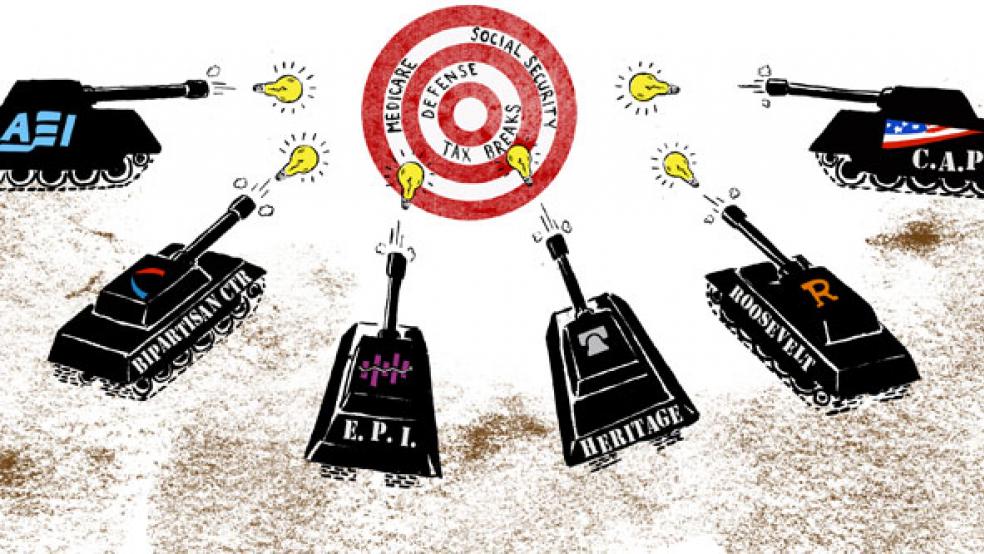

Interviews with representatives of the six groups, whose work on this project was underwritten by grants from the Peter G. Peterson Foundation , reveal that though their philosophical differences about the government’s role are great, they all agree that current fiscal policy is not sustainable. The groups, from left to right, include: the Roosevelt Institute Campus Network; the Economic Policy Institute (EPI); the Center for American Progress http://www.americanprogress.org/ ; the Bipartisan Policy Center ; the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) and the Heritage Foundation http://www.heritage.org/. “Everyone is in agreement that in the long run deficits have to be below the more pessimistic projections,” Michael Ettlinger, vice president for economic policy at the progressive Center for American Progress, said in an interview.

And the groups also share a greater appreciation for the difficulties that legislators and the White House confront in trying to reach agreement on a plan to bring down the spiraling national debt. A bipartisan group of six House and Senate members, led by Vice President Joseph Biden, planned to meet again this afternoon in search of a compromise to cut more than $1 trillion in spending and raise the $14.3 trillion national debt ceiling before the Treasury runs out of borrowing authority Aug. 2. Another bipartisan group of senators has struggled to find consensus on a more comprehensive, long term plan for controlling the deficit.

“The difficulty of the choices was brought home to us more vividly than we had previously realized,” Alan Viard, a resident scholar at the conservative American Enterprise Institute, noted in an interview.

Still, the differences in approach among the groups are far greater than areas of agreement, Viard added. “If anybody thought that there would be some eureka moment where liberals and conservatives would just suddenly say, `Oh, here’s the way we can do it — let’s get together and do that today’ — of course, it is not going to [happen].”The foundation assignment given the groups was to develop a plan that achieves fiscal “sustainability” and budgetary and programmatic targets for achieving the goal. The plans had to be specific enough that a group headed by former Congressional Budget Office official Barry Anderson could assess them for their budgetary impact over the next 10 to 25 years.

Many economists agree that the ratio of government debt to gross domestic product (GDP) is an accurate gauge of a nation’s fiscal health. The six groups’ projected levels of federal debt to GDP varied significantly, from 30 percent for the more conservative organizations seeking deep spending cuts, to 82 percent for the most liberal groups that favor more government spending.

However, all six organizations support maintaining a social safety net for those who need it, according to a Peterson Foundation analysis. Some of the groups would make social programs more generous than others, and there are differences in the specific policies; but all preserve a role for government in maintaining health and retirement security for low-income citizens. “Further, by putting America on a fiscally sustainable path, all of the plans help to ensure that safety nets will be more secure for future generations,” the analysis stated.

Huge Range in ‘Adequate’ Safety Net

In surveying the six proposals, Ettlinger said there’s “not much” overlap in their approaches, and he even questioned the extent of their agreement on safety nets. “The notion that everyone agreed on a safety net – I guess in theory that’s true, but there is a huge range in what people consider to be an adequate safety net.”

John Irons, the research and policy director of the liberal Economic Policy Institute, echoed Ettlinger. “There was a rhetorical consensus [on safety nets]; I’m not sure there was a policy consensus. I am thinking Heritage specifically — the gap between rhetoric and policy is probably the largest.”

On that issue, Zach Kolodin, director of the Future Preparedness Initiative at the Roosevelt Campus Network, questioned whether shifting Medicaid’s federal-state relationship to one in which states get more latitude in designing health services for the disabled and elderly — the Heritage approach — would provide sufficient protection for the vulnerable.

“When state budgets get smaller, people get wiped off the Medicaid rolls. People get pushed off of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families. I actually don't think low-income families can feel secure under that kind of regime,” he said during a panel discussion. “We need to have an honest conversation-- I think it's very rude, right—to say that we might expect low-income families to not actually get the benefits that they're promised.”

The groups’ philosophical differences became even more apparent as they were pressed during the panel discussion on their approaches to the right mix of spending cuts and higher taxes. Ettlinger bragged that the Center for American Progress’s plan was “unique” because, he said, “we completely balance the budget, without socking it to the middle class.”

He noted that the in the past 30 years, the middle class “has hardly benefited” in income growth, whereas the wealthiest individuals have had huge growth. “You have to look at where the money is,” he said during the panel discussion. “People keep talking about distributing the pain fairly. Well, by this measure, the middle class doesn't really need any more pain. And I think that the right place to look to get revenue-- additional revenues is, in fact, the top.”

That approach is reflected in CAP’s proposal to raise the top tax rate to the level during the Clinton Administration and to impose a five percent surtax on ordinary income over $1 million.

But Joe Minarik, who represented the Bipartisan Policy Center and is senior vice president of the Committee for Economic Development, disagreed that fiscal sustainability could be reached without some middle-class pain. Noting that the BPC plan essentially protects those at the low end of the income scale, he added that the tax burden on those above the bottom 20 percent income level would gradually increase. “Unfortunately, we've got a very big problem,” he said.

Talk of more taxes is entirely wrongheaded, Butler said in the interview. “In the big picture, what you see on the left, to be honest, over the next 25 years is they want to move the United States to spending and tax levels like Europe,” he said. “We want to keep them at levels that Americans have basically said over the last 50 years is where they want to see government.”

To that end, under the proposal that Heritage outlined, federal revenue levels in 25 years — by 2035 would be 18.5 percent of GDP, far lower than EPI’s projected revenue level of 24.1 percent of GDP.

Given the philosophical divide among the groups, did this endeavor simply produce predictable results? Several of the participants insisted that it was illuminating because they had to produce sufficiently detailed plan that were subjected to the same analytical rigors of legislation proposed on Capitol Hill. “There is a huge value to focusing everybody to put numbers on a piece of paper,” Ettlinger said in the interview. “We see the consequences of different organizations’ values and the things they prioritize.”

Irons agreed in the value of the exercise, but he also was somewhat disappointed in the results. “I was hopeful there would be more room for agreement going into this, but there are fundamental differences that people have.”

The Fiscal Times, an independent news and opinion service, is funded by Pete Peterson, but is not affiliated with his foundation.

Related Links:

U.S. Billionaire’s Debt Crusade Finally Center Stage (Wall Street & Technology)

Senate Republicans Say ‘No’ to Ryan Plan (NPR)