A new study suggests it is highly unlikely that the Treasury would actually default on its debt beginning in early August if the White House and Congress fail to agree on a long-term deficit-reduction plan and an increase in the current $14.3 trillion limit on government borrowing.

A respected bipartisan group says that, based on current projections of tax revenues for August, the Treasury would have ample funds to cover the interest on Treasury securities, as well as issue Social Security and unemployment checks, make Medicare and Medicaid payments, and reimburse Defense Department vendors throughout the month.

But the analysis by the Bipartisan Policy Center strongly warns that failure to raise the debt ceiling by the August 2 deadline set by Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner might make it more difficult for the government to roll over or refinance almost $500 billion of short-term and long-term debt coming due without paying higher interest rates. And it would immediately force the Treasury to slash spending by 44 percent for most other government agencies and programs, including military pay, veterans affairs programs, criminal justice programs and education.

Jerome (Jay) Powell, a former Republican Under Secretary of the Treasury for Finance and chief author of the study, said Tuesday that “We don’t think it’s likely” the Treasury would default on its bonds in the event Congress refuses to raise the debt ceiling, but that “it’s not outside the range of possibility.” However, he warned that failure to raise the debt ceiling by the deadline would almost certainly undermine international investor confidence in the government, prompt the three major rating agencies to put the U.S. on a watch list to possibly downgrade its AAA bond rating, and force widespread curtailment of government services that could force layoffs and hurt the economy.

“It’s fair to say beyond dispute the results would be chaotic,” Powell told reporters at the center’s Washington headquarters. “The Treasury would be picking winners and losers, the public is going to be in an uproar, you can imagine litigation and you can be absolutely certain of intense global media focus.

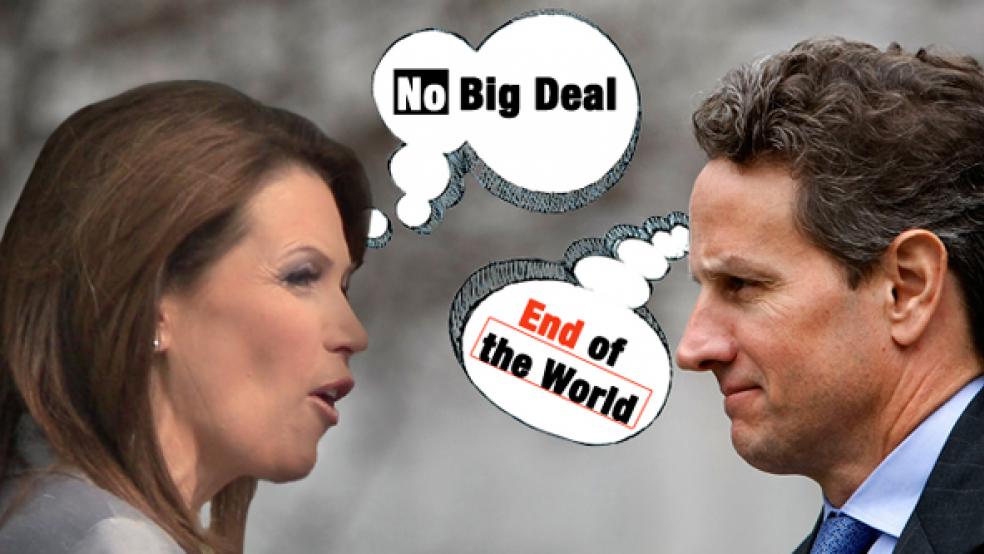

President Obama’s efforts this week to break a deadlock in budget talks between Demoats and Republicans underscores the growing concern that without a major deficit reduction deal within the next four weeks, the Treasury is headed for an unprecedented debt crisis. Geithner and Federal Reserve Board Chairman Ben Bernanke have repeatedly warned that failure to raise the $14.3 trillion debt ceiling would force the first default in history and touch off a cataclysmic international financial crisis.

While many budget and political experts say it’s unthinkable that Congress would risk a default, a substantial number of conservative Republicans, including presidential candidate Michele Bachmann, insist the Treasury could temporarily get by if it made tough-minded decisions on which bills to pay and which to set aside. "It isn't true that the government would default on its debt," Bachmann, a three-term House member from Minnesota, said over the weekend, adding that the Treasury could “pay the interest on the debt first, and then, from there, we have to just prioritize our spending."

House Speaker John Boehner, R-Ohio, told Sean Hannity of Fox News on Tuesday: “Dealing with this deficit problem is far more important than meeting some artificial date created by the Treasury Secretary. We cannot miss this opportunity.”

But former Senate Budget Committee Chairman Pete V. Domenici, R-N.M., a senior fellow at the Bipartisan Policy Center, said: “It is beyond my comprehension as to what an elected official could get out of thinking that we should in fact default or that default isn’t very significant.”

“The truth of the matter is that default on this debt means your country could indeed be at risk and things could change economically way beyond what you expect and be irretrievable in terms of the negative effect on us,” Domenici added.

The global financial community is watching closely as the Obama administration and congressional Republican leaders struggle to reach agreement on a package of savings in the range of $1.6 trillion to $1.7 trillion over 10 years and avert the possibility of a debt-ceiling crisis. Trading in credit-default swaps—which are essentially financial insurance policies—has picked up, while the price of protection against default has risen. “It scares the hell out of me that someone is taking out insurance on U.S. bonds,” Stephen E. Bell, a former Senate aide to Domenici and former managing director of Salomon Brothers Inc., told The Fiscal Times.

Obama met Monday with Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, D-Nev., and Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., to discuss budget issues, but with no indication of movement. Before a Republican walkout last Thursday, budget talks overseen by Vice-President Joe Biden had made significant progress towards a budget deal. But Republicans are insisting on more in spending cuts than the Democrats are willing to go along with, while rejecting Democratic demands close loopholes and raise tax revenues as part of the overall mix.

McConnell described his deficit meeting with the President on Monday as a “good discussion, but blamed Democrats for a lack of progress and held a hard line that any package including tax increases is dead on arrival. “The talks continue and we are hopeful that we will be able to take advantage of the opportunity presented to us by the President’s request to raise the debt ceiling,” McConnell told reporters on Capitol Hill.

“The bigger the package, the better,” McConnell said, referring to the size of the spending-cut package that Republicans want to accompany any increase in the debt ceiling. Republicans insist that the level of cuts must match the increase in the debt ceiling dollar for dollar.

Mark Zandi, chief economist with Moody’s Analytics, said at a breakfast hosted by the Christian Science Monitor that failure to raise the ceiling “would do serious damage. Markets are going to start going south.”

Unless Congress agrees to raise the debt ceiling, the Treasury will reach a point sometime between August 2 and August 9 when it will no longer be able to pay all of its bills and obligations without additional borrowing authority, according to the Bipartisan Policy Center study. The Treasury will take in an estimated $172.4 billion in tax revenues that month but will have an estimated $306.7 billion of overall obligations—a shortfall of $134.3 billion or 44 percent.

Among the biggest obligations facing the Treasury in August will be $29 billion in interest on Treasury securities, $49.2 billion in Social Security benefits, $50 billion in Medicare and Medicaid payments, $31.7 billion in defense contractor payments, and $12.8 billion of unemployment insurance benefits.

If the government used available tax revenue just for those six major programs and costs, it would have nothing left to fund virtually the rest of federal operations--an impossible situation that would necessitate unprecedented government spending tradeoffs until the debt ceiling crisis subsided.

“We can play this game of chicken and egg, but at the end of the day we’re going to have to pay our bills and we’re going to have to have a comprehensive plan to deal with the debt threat, because it does threaten the economic security of this country,” Senate Budget Committee Kent Conrad, D-N.D., told MSNBC yesterday.

Related Links:

Failure to Raise the Debt Ceiling Could Limit Social Security (USA Today)

Possible Scenarios for U.S. Debt Limit Talks (Reuters)

Debt Ceiling Delay Would Be Chaotic (CNN)