In a state known for producing colorful political personalities, Texas Gov. Rick Perry still stands out. In a Houston stadium half-filled with Christian conservatives, he leads a prayer service calling on Jesus to bless and guide the nation’s military and political leaders as he appeals to the audiene for votes.

He doesn’t just want to lower the federal income tax. He wants to repeal the 16th amendment that makes it possible. And while he’s at it, he’d like to eliminate the corporate income tax, the estate tax and the capital gains tax.

On the 2008 campaign trail where he backed former New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani, he publicly trashed his predecessor as Texas governor, who was then sitting in the White House. “In ’95, ’97, ’99, George Bush was spending money,” he told house party guests captured in widely circulated YouTube video. “George has never, ever been a fiscal conservative.”

He doesn’t spout the social tolerance or compassionate conservatism of his predecessor, either. Perry supports an amendment that would ban same-sex marriage. And to the cheers of pro-life activists, he has signed more legislation restricting abortions than any governor in the country. Earlier this year, he signed a bill that requires Texas women get sonograms prior to an abortion so their doctors can offer to let them see or listen to the fetal heartbeat.

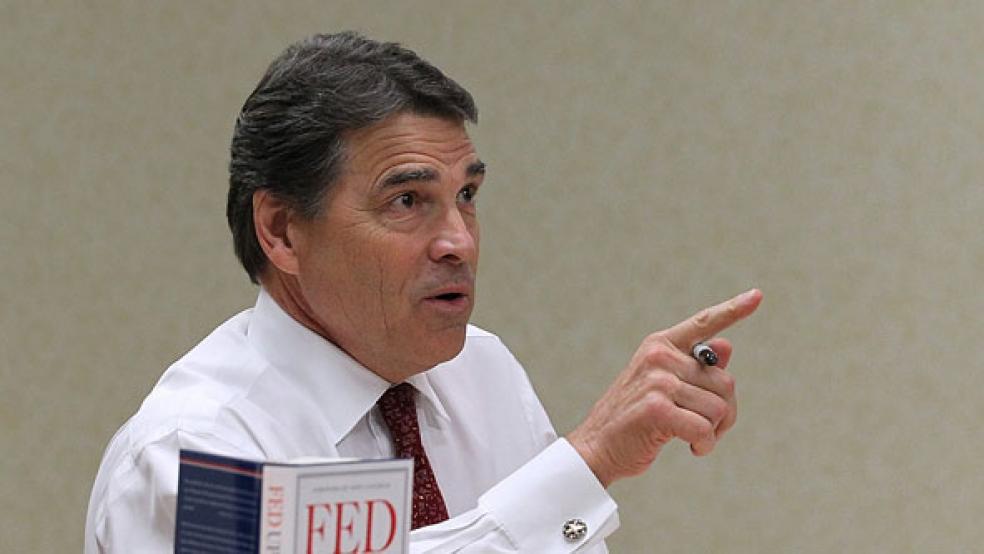

Perry, 61, may affect the down-home manner that Americans have come to expect from politicians from the Lone Star state, especially when they seek higher office. He wears cowboy boots to the office and packs a laser-sighted pistol while out walking the trails of his native west Texas to fend off snakes and other wild animals.

But underneath Perry’s back-slapping ways and folksy homilies are a political toughness and a fundraising acumen that has kept him atop the rough-and-tumble Texas political scene for more than a decade, making him the longest serving governor in state history. In the process, the one-time Democrat has demolished what was left of the centrist elements in the Texas Republican Party, rebuffing former Sen. Kay Bailey Hutchison’s primary challenge in 2010 and earning the enmity of the Bush clan, which had backed her.

The Texas money men and political consultants behind his campaign believe that his toughness – not to mention his dark-haired good looks – will carry Perry to victory in the upcoming Republican primaries against a field of what most political observers consider either bland or unelectable competitors. Perry can lay claim to the same executive experience as former governors Mitt Romney, Tim Pawlenty and Jon Huntsman, Jr. and businessman Herman Cain.

He has the conservative credentials on social and economic issues to compete for the affections of Republican primary voters who might otherwise back candidates like Michelle Bachmann, Rand Paul and Rick Santorum, whom most political pundits consider unelectable. And he doesn’t carry any of the Washington baggage of former House Speaker Newt Gingrich.

Many of the same forces that elevated Bush to high office have already coalesced behind Perry’s late-blooming candidacy, which he announced in South Carolina Saturday. Deep-pocketed Texas oil money, led by the right wing Koch brothers, earlier this year helped launch Texans for Rick Perry Political Action Committee. The Kochs have also been major funders of the Tea Party movement. In June, while Texas suffered through some of the worst wildfires in state history, Perry flew off to a secret rendezvous in Colorado to speak to a closed-door meeting convened by the Kochs.

Phil Gramm, another former Texas Democrat and an outspoken champion of the financial deregulation that nearly sank the U.S. economy in 2008, he also been a major Perry backer. Gramm has donated more than $600,000 to Perry over the course of his career.

Perry, who raised more than $100 million in campaign contributions as governor, has over 200 “mega-donors” who’ve donated $100,000 or more. Individuals and committees associated with energy, natural resource extraction, and waste disposal companies lead the parade, according to the watchdog group Texans for Public Justice.

Perry’s not shy about helping out the economic interests of his donors. Perry’s second leading moneyman is Harold Simmons, owner of Waste Control Specialists. The company hopes to build a controversial nuclear-waste dumpsite in the western part of the state. Perry appointees recently signed off on the plan despite the objections of state environmental regulators.

Perry’s political ascent parallels the path pursued by many southern conservatives who began their careers as Democrats and wound up on the extreme right wing of the Republican Party. He is the Eagle Scout son of a Democratic politician in the small town of Paint Creek, which wasn’t even on the map until he put it there while governor.

He attended Texas A&M University, where he earned middling grades and graduated with a degree in animal science. After graduation, he joined the Air Force, leaving after five years with the rank of captain to join his father in cattle ranching in West Texas.

Perry married a childhood friend Anita Thigpen in 1982 and two years later entered politics by winning a seat in the state legislature, where he served three terms. In 1988, he ran the Texas campaign for Al Gore, who that year carried the banner for southern conservative Democrats.

But the following year, like many southern conservatives, he switched parties after being encouraged by political kingmaker Karl Rove to challenge populist Democrat Jim Hightower for the high profile Agricultural Commissioner seat. He won after high-ranking officials in Hightower’s office became embroiled in a bribery scandal tied to campaign contributions. Hightower partisans later complained the affair had been engineered by Rove and the first Bush administration’s Justice Department. In 1998, Perry narrowly won a race for Lieutenant Governor and stepped into the governor’s role after Bush became president in 2000.

While in office, he’s moved right on many issues. Early on in his 10-year tenure, he was sensitized by employers to the need for a steady source of cheap labor and backed the right of illegal immigrants’ children to receive scholarships to attend state universities. More recently, though, he has backed giving police the power to stop people without cause to demand proof of citizenship.

Perry, a lifelong Methodist who regularly attends an evangelical mega-church near his home in West Austin, has been speaking and preaching in sanctuaries throughout Texas since the early 1990s, often blurring the line between politics and religion. “There’s been a significant attempt by him and his staff to reach out to conservative Christian leaders and it’s now going to a new level,” Mat Staver, founder and chairman of Liberty Council, a conservative Christian advocacy group, told CNN.

Perry’s opposition to same-sex marriage and his anti-abortion credentials will undoubtedly give him a leg up on former Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney, who is considered the front runner. Romney is unpopular among many conservative Christian activist groups because of his onetime support for abortion rights and for the Massachusetts health care law, which requires all residents to carry health insurance.

Perry is likely to stress what he considers Texas’ strong economy on the campaign trail even though the state’s unemployment rate of 8.2 percent ranks it 25th in the nation – squarely in the middle of the pack. The state also has 26 percent of its population without health insurance, the highest in the nation, while its education performance has drawn criticisms from Dallas Federal Reserve Bank president Richard W. Fisher, who recently complained that the state was “dead last in the percent of the population age 25 and older that graduated from high school, 37th in percent of population enrolled in degree-granting institutions, 35th in academic research and development, and 41st in science and engineering degrees awarded.”

With the encouragement of business leaders in the state, Perry in 2006 did pull together a school reform finance package that lowered local property taxes and replaced them with a 1 percent franchise tax on business “margins” – structured to avoid the use of the phrase “income tax.” That subterfuge won plaudits from anti-tax lobbyist Grover Norquist.

Despite his hard-right stands on social and economic issues, Perry has been described by bloggers and Texas citizens as having a demeanor that can appeal to centrist voters. Political operative Reggie Bashur, who’s worked with Perry, said, “He’s got a tremendous personality, he likes people, he can talk to an individual one on one, he gives a good speech, (and) he carries a strong message.”