In 2007, Ashley Gordon was nearing graduation at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and had no idea what she was going to do. With a double major in math and biology, she planned to move back in with her parents and support herself with babysitting jobs until she could find a real work. But in her senior year she came across an AmeriCorps booth at a career fair and was immediately intrigued. “I thought, this is something I’d like to do … and it’s doing something productive with your life. It’s not like I was going to take a year off and just watch TV.”

With student debt now approaching 1 trillion and employment among young adults at 55.3 percent -- the lowest level since World War II -- recent grads are moving back home en mass and struggling to find purpose or direction. “There is a massive rate of unemployment in this demographic,” says Greg Peppers, executive director of Service Nation, a campaign to increase service opportunities. “And every year that [these graduates] are out of work, they become less competitive … We have an entire generation of young people about to be left behind.”

So, many college graduates are looking to options like internships, volunteering, and service programs to fill their time.

AmeriCorps, the government service program established in 1993 by President Clinton, dispatches thousands of volunteers across the country in fields like education, disaster relief, park beautification, and infrastructure projects for a small stipend and modest living allowance. In 2009 it saw online applications triple. AmeriCorps currently receive more than 530,000 applications for just over 80,000 spots, a 15 percent acceptance rate. Teach for America, which employs recent grads for two-year terms in inner-city schools, is even tighter, with 47,000 college grads vying for a mere 4,600 positions, according to Peppers. The Peace Corps saw a 16 percent jump in applications in 2008 and an additional 18 percent increase in 2009. “Volunteering, especially for young labor market entrants, is a great way for workers to gain skills, do something valuable, and wait out the recession," says Yale University labor economist Lisa B. Kahn.

Many recent grads are seeing doors open as a result of these programs. Some corporations look to them for future employees—Comcast even promises to interview anyone who graduated from City Year, which places volunteers in urban, low-income schools. “These people can find themselves with positions of management leading volunteer teams,” Scott says. “In many cases, it’s much more experience than they would get in any entry-level cubicle job.”

"Searching for jobs in recessions is very damaging to your long-term labor market experiences," says Kahn. "It is possible that people would be better off sitting on the sidelines until the economy recovers. But that looks very bad on a resume. Employers like to see workers doing something.”

It’s not just the economy that is driving people to serve, however. “These individuals came of age in a post-911, post-Katrina era, with two presidents who’ve said that one of the ways you can deal with this is to give back,” says Ben Duda, executive director of AmeriCorps Alums. President George W. Bush heavily supported service programs in the wake of 9/11, increasing the budget for both the Peace Corps and AmeriCorps. And in 2009, President Obama signed into law the Serve America Act , laying out a plan to increase AmeriCorps positions from just over 80,000 to 250,000 by the year 2017. Obama also promised during his 2008 campaign to double the size of the Peace Corps, to 16,000, by 2011. He modestly increased funding for fiscal year 2010 and 2011 and is proposing another slight increase for 2012. But the president’s 2011 budget would downsize the Peace Corps to 11,000 by 2016.

“The future of our nation depends on the soldier at Fort Carson,” Obama told a crowd at the University of Colorado, Colorado Springs in July 2008, “but it also depends on the teacher in East L.A, the nurse in Appalachia, the after-school worker in New Orleans, the Peace Corps volunteer in Africa, and the Foreign Service officer in Indonesia. Americans have shown that they want to step up, but we're not keeping pace with the demand of those who want to serve.”

Now, however, there is a backlash against such lofty ideals. Although the Senate’s 2009 Serve America Act passed easily, the growing debt crisis and language suggesting mandatory service in a 2009 House proposal called the Generations Invigorating Volunteerism and Education Act (the GIVE Act) have sparked criticism and proposals to slash AmeriCorps’ budget.

Many opponents argue a larger AmeriCorps could become another wasteful government-run program, and any forced service is contrary to the idea of charity. Although the mandatory language was stripped before the bill passed, AmeriCorps and similar programs saw a $23.2 million budget cut in April of this year, with House Republicans pushing for more cuts.

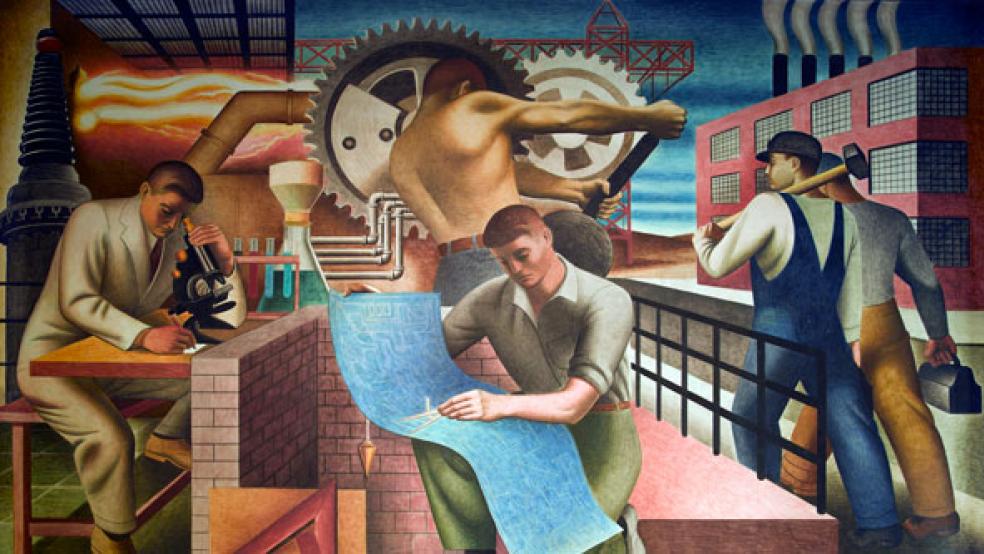

But more service employees could potentially save the government money, according to Peppers at Service Nation. He says every federal dollar invested in national services yields more than $2 in goods and would-be labor costs from workers in fields like education and disaster relief. For example, FEMA Disaster Assistance Employees make anywhere from $11.29 to $42.03 an hour—with overtime—depending on their skill sets. AmeriCorps workers who aid with disaster relief receive a small $4,000 stipend for 10 months, plus modest room and board. Proponents also point out that during the Great Depression, Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps, similar to AmeriCorps, put 250,000 young men to work and helped cut the unemployment rate in half.

And for Gordon, the program helped give her direction. She worked on several different projects during her 10-month stint, including Habitat for Humanity in Louisiana and disaster relief after Hurricane Ike in Texas. She left the program with a host of new friends, a $5,500 grant to put towards graduate school, and a clearer idea of where she wanted to go next. “I got to travel a lot,” Gordon says. “I got to see a lot of the country in its natural form and beauty.” The experience led her to look into sustainability and a master’s degree in engineering, which she is now working towards at Virginia Tech. “I really wanted to help preserve and project nature so that so other people could have the same experience that I had.”