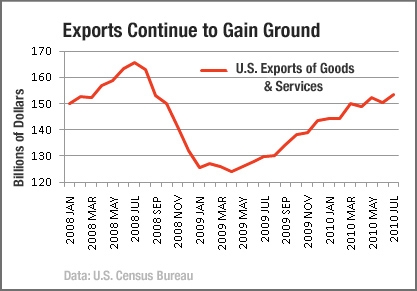

• The July trade gap narrowed to $42.8 billion • Inflation-adjusted exports rose 16 percent from last year • Overseas shipments of autos jumped 55 percent |

Economists went bug-eyed a month ago when government data showed the June trade deficit had widened 18 percent from May. It was the sharpest monthly increase on record, and far greater than expected. The news sent analysts scurrying to cut their forecasts for economic growth, while raising fears about the global recovery and making President Obama’s initiative to double exports in five years look like a pipe dream.

The problem, the economists said, was that those numbers didn’t make sense. U. S. demand was not strong enough to draw in a new wave of imports, which the June report showed, and global growth had not slowed so much as to cause exports to fall off a cliff, as the data also suggested. Fed chief Ben Bernanke even weighed in, saying the huge widening “seems to have reflected a number of temporary and special factors.” As it turns out, the economists were right, and the outlook for U.S. trade is a lot brighter than the June numbers implied.

The July trade gap for goods and services narrowed sharply to $42.8 billion dollars, from $49.8 billion in June, the Commerce Deptartment said last Thursday, largely reversing the June spike. Imports fell by $4.2 billion in July, backtracking two-thirds of the June increase, while exports rose $2.8 billion, more than recouping their June losses. The turnaround, along with other better-than-expected reports in recent days on payrolls, unemployment claims, and manufacturing activity, buoys the economic outlook for the second half.

A bigger trade deficit subtracts from GDP growth. The wider gap in the second quarter pulled the quarter’s growth rate down by 3.4 percentage points, the most in any quarter in 63 years. The July trade report means that a subtraction, if any, in the current quarter will most likely be small. Economists at Barclays Capital say the report is consistent with their forecast that GDP growth will pick up to 2.5 percent in the third quarter, from 1.6 percent last quarter. Analysts at Morgan Stanley, who believe that trade will be a net plus for growth in the second half, have nudged up their third-quarter projection to 2.4 percent, from 2.1 percent.

As fears that the U.S. could slip back into recession are fading, so are worries that the global economy could stall out. Global growth is clearly slowing, but much of that downshift is to be expected. Early in a recovery, businesses boost output to replenish depleted inventories, but once stockpiles are back in balance with sales, output growth falls back into alignment with the pace of demand. And so far, global demand, while far from strong, appears to be holding up fairly well.

Among major economies, real GDP in the euro zone and in the U. K. grew 3.9 percent and 4.9 percent, respectively, in the second quarter, both with healthy contributions from domestic demand. Growth in Japan, which initially appeared to stall last quarter, was revised to show a 1.5 percent advance, partly reflecting stronger business outlays, and reports suggest third-quarter growth will be much stronger. Even in the U.S., growth in inflation-adjusted consumer spending is tracking close to 2 percent this quarter, say economists at J. P. Morgan Chase, which would match the pace in both the first and second quarters.

In the developing countries, meanwhile, growth is slowing from torrid to merely strong. China, where growth from the same period last year slowed to 10.3 percent in the second quarter from 11.9 percent in the first quarter, is leading the pace in Asia and adding support to Japan. Banks in Asia are not seriously impaired right now, and lending is flowing. Much the same is true for Latin America. “Like most Asian economies, Latin countries were not overly leveraged coming into the 2008 financial crisis,” say economists at Wells Fargo Securities in their latest global outlook.

Through July, inflation-adjusted exports from the U.S. were up 16 percent from the same period last year, thanks largely to growth in emerging market (EM) economies. U.S exporters are benefiting from a global upswing in capital spending, especially infrastructure projects and the new influence of EM consumers. Through July, exports of U.S.-made capital goods and industrial supplies accounted for nearly 60 percent of the overall increase in U.S overseas shipments. Foreign sales of autos, which contributed one-quarter of overall export growth, rose 55 percent from last year.

Overseas shipments will continue to get a boost from solid, if unspectacular, global growth, while the decline in the dollar over the past three months also will help. A cheaper dollar makes U.S. goods and services more competitive in overseas markets.

China and other nations that sharply bend their policies to boost their competitiveness will continue to present obstacles to U.S. trade. However, despite these tactics, Brookings Institution analyst Bruce Katz notes that the U.S. remains the world’s largest exporter, largely because of its competitive positions in high-value technology goods, and especially services, which now make up 30 percent of America’s exports. Obama’s goal of doubling U.S. exports in five years means that inflation-adjusted shipments have to rise 15 percent per year to meet that target. The July trade data confirm that the U.S. is already exceeding that pace, even in an only moderate global recovery.