• China's econmy grew 10.3 percent in 2010, inflation grew 5.1 percent. • 14 of 21 emerging-market central banks hiked rates in the past two months. • British inflaton could exceed 4 percent this year. |

After cooling down a notch last year, the global recovery is heating up again. A spate of stronger-than-expected economic reports around the world shows that growth is speeding up and broadening across countries and industries. The benefits for global trade, especially for U.S. exports, are clear, but this new phase of the upturn also brings new risks. Inflation is picking up in China and other emerging-market economies, as well as in Britain, and the world’s central banks have taken notice. So have investors, who are increasingly concerned that keeping inflation in check will require higher interest rates, which could put a new chill on the recovery.

“Global economic activity appears to be accelerating sooner and by more than we had anticipated,” economists at J.P. Morgan said in a recent research note. Unlike 2010, when growth was driven mainly by manufacturing, as businesses rebuilt their inventories, this new strength reflects a pickup in both manufacturing and services, suggesting a much broader upturn in global demand. Economists say this duel strength is reminiscent of mid-2003, when global GDP boomed at about a 5 percent clip for three quarters in a row.

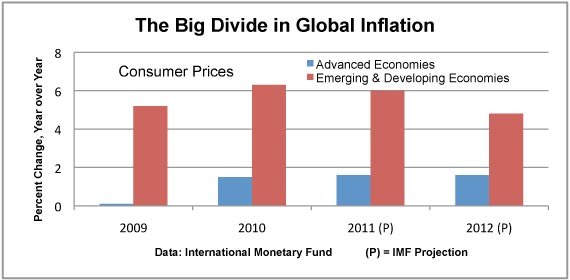

This global reacceleration, in which the U.S. is taking a leading role, raises a new question: Does the world face looming inflation? The pressure is greatest in emerging-market economies, which barely felt the financial crisis and recession. They began the global recovery already using a relatively high percentage of available workers and production facilities, and the upturn quickly took up much of what slack was remaining, creating upward pressure on prices. The recent surge in commodity prices, especially in food and energy, has added even more steam.

The spotlight has been on China, whose GDP grew 10.3 percent in 2010 and is expected to slow only slightly in 2011. Fueled mainly by rising prices for food and energy, Chinese inflation jumped to 5.1 percent in January, from 1.5 percent in January 2010. China’s central bank raised its benchmark interest rates on Feb. 8 for the third time since October, and a further increase seems likely in an effort to quell inflation and control asset bubbles. It’s not just China. J.P Morgan analysts say that 14 of the 21 emerging-market central banks they follow have raised rates in the last two months.

But just as the global economy suffered a two-tier recession, which slammed advanced economies but barely touched emerging-market nations, the inflation outlook is also two-tiered. Growing price pressures in the developing world are not being reinforced by upward price pressures from developed economies. Amid continued high unemployment, business conditions in the U.S., the euro zone, and Japan will not support a sudden and rapid rise in pricing power. “The picture is quite different in advanced economies, where still-ample economic slack and well-anchored inflation expectations will generally keep inflation pressures subdued,” according to the Jan. 25 update of the International Monetary Fund’s World Economic Outlook.

Britain is the exception. Its economy faces a nasty combination of rising inflation and sluggish growth. British GDP actually fell in the fourth quarter, while inflation picked up to an eight-month high of 3.7 percent as of December. Bank of England Governor Mervyn King has said the pace could rise above 4 percent, more than double the central bank’s 2 percent target. Monetary policymakers at their meeting on Feb. 10 left their benchmark interest rate at a record low 0.5 percent, but economists believe Britain will be the first advanced economy to lift rates, perhaps as early as mid-year.

The potential for recent spikes in food and energy prices to be passed along into prices of other goods is generally not as great in developed economies as it is in the developing world. Demand for goods and services in emerging markets is already running hot, and food and energy account for a large share of spending. Food alone accounts for one-third of the Chinese consumer price index, say economists at Wells Fargo Securities, more than twice the relative importance of food in the U.S. CPI. However, in both developing and advanced economies rising food costs can also dampen growth, given the hit to household purchasing power.

In addition to China, several developing nations, such as India and Brazil, are already lifting interest rates. China analyst Jian Chang at Barclays Capital believes that China’s rate hikes, including one more increase, will help to prevent runaway inflation and the need for more or larger increases that could cripple Chinese growth and damage the global recovery.

For now, at least, core inflation around the world, which excludes energy and food, is generally subdued. In the U.S., core inflation in December was running at a mere 0.8 percent, with the overall rate at 1.5 percent. In the euro zone, January data show the core rate at 1 percent, well below the 2.4 percent total. Even in China, core inflation through January is only about 2 percent and has shown a much more modest acceleration, compared with the 5.1 percent rate for overall prices.

Clearly, prices of food and energy matter, but they are often subject to temporary volatility from seasonal spikes and supply issues, which have been a major factor in the recent surge in food prices. Last year, drought and wildfires in Russia destroyed crops and led to a ban on grain exports. Historic flooding in Australia, a major commodities producer and supplier to China, disrupted shipments of coal, wheat, and sugar. This mix of supply shocks is unlikely to happen two years in a row, and many economists believe food inflation will subside, perhaps substantially, over the coming year.

For now, the two-tier nature of the inflation outlook puts the onus on the cntral banks of emerging-market nations to assure that their economies do not overheat. But even in advanced economies, which are still running policies involving ultra-low interest rates and heavy government borrowing, there is a risk that the costs of these policies may outweigh the benefits. In the coming year, investors will be on pins and needles hoping the world’s central banks make the right choices.