While we continue to grieve for the victims of the Japanese earthquake and its aftermath, it is perhaps time to cast a colder eye on the consequences of the country’s worst disaster since the atomic attacks of 1945. What is this calamity going to mean for the Japanese economy? Will there be international repercussions? Will this disastrous convergence—earthquake, tsunami, nuclear-power accident—cause Japan to alter course fundamentally?

What you get when you explore the universe of market analysts, brokerage newsletters, think tanks, scholars, commentators, and assorted others is generally some variation of uncertainty dressed up to imply that there is something more than guesswork available just now.

Still, though the Fukushima nuclear plant is not yet stable and few hard economic facts are available, some things are already evident. Chief among them is that the Japanese economy will take a short-term hit but will not falter long: If history is any guide, it may enter a post-quake period of higher growth. Yes, there will be some global fallout—supply-chain disruptions, reduced Japanese capital flows overseas—but none of it justifies any kind of nightmare scenario. And no, Japan is not going to reinvent itself now any more than the U.S. did after Hurricane Katrina six years ago.

“It’s a rich, big, competent country with a lot of resources and knowledge,” says Arthur J. Alexander, a professor at Georgetown University and a longtime Japan watcher as president of the Japan Economic Institute in Washington. “Things can come together rather quickly, and I expect them to.”

Japan was in the midst of a brisk recovery prior to the quake: Even with a weak fourth quarter, GDP expanded by 3.9 percent in the third quarter last year—the best performance in the G-7. Many economists had projected growth for the first half of this year at 2.2 percent to 2.5 percent, but these will fall. Look for zero growth in the first two quarters of 2011; Nomura, whose thinking was more conservative to begin with, revised its yearly growth projections two weeks ago, from 1.3 percent to 0.9 percent.

Still, this cannot be expected to alter Japan’s course. Neither will a tax increase, which is widely expected as one source of reconstruction funds: Japanese taxes as a percentage of GDP are about a third—relatively low by international standards (though not by America’s), so there is political room for a “disaster tax.”

Internationally, there have already been some disruptions in supply chains such that automakers from Detroit to Belgium have had temporary shutdowns due to a lack of components. Toyota announced this week that it is suspending all U.S. operations—effectively idling a top manufacturer in the U.S. One detail tells the story here: A Hitachi plant in the quake-affected zone produced about 60 percent of the world supply of an air sensor used in auto engines; that plant is out of operation.

These are the kinds of micro problems Japanese companies will have to solve by way of alternative suppliers, alternative transport routes, alternative components, and the like. Last week both Toyota and Nissan announced that their domestic plants were going back into operation after some shutdowns—which offers one suggestion of how quickly the industrial consequences of the quake can be addressed in a sophisticated, densely layered economy.

In the old days, correspondents and share analysts in Tokyo used to gather for beers and ponder what it would be like if “the big one” hit Tokyo and Japan started bringing back all its overseas investment funds—notably, of course, its immense holdings of U.S. Treasuries. Now this talk is back, and it is as overblown today as it was twenty years ago.

Japan has run a current-account surplus every year since 1980, meaning it is a net exporter of capital to the benefit of the U.S. and others. This surplus was $5.6 billion last year, the Finance Ministry just announced, down (for a variety of reasons) by nearly half from 2009.

It is another certainty that these capital outflows will now slow down as Japan invests more at home to rebuild disrupted zones, sectors of the economy, and infrastructure. But a slowdown is not a withdrawal. Equally, reduced investments abroad will reflect not a policy at the Finance Ministry or the Bank of Japan but a thousand decisions made by Japanese savers, companies, banks, and insurers. (Current estimates of insurance liabilities run to $30 billion or so.)

As to truly lasting effects, if there is one, it could prove to be political. Japan is now governed by the perennial opposition party, the Democrats, and if they manage this calamity competently, it may well convince more voters that leaders other than the long-governing Liberal Democrats are capable of running Japan. So far as developing a two-party system out of an earthquake goes, silver linings do not get odder.

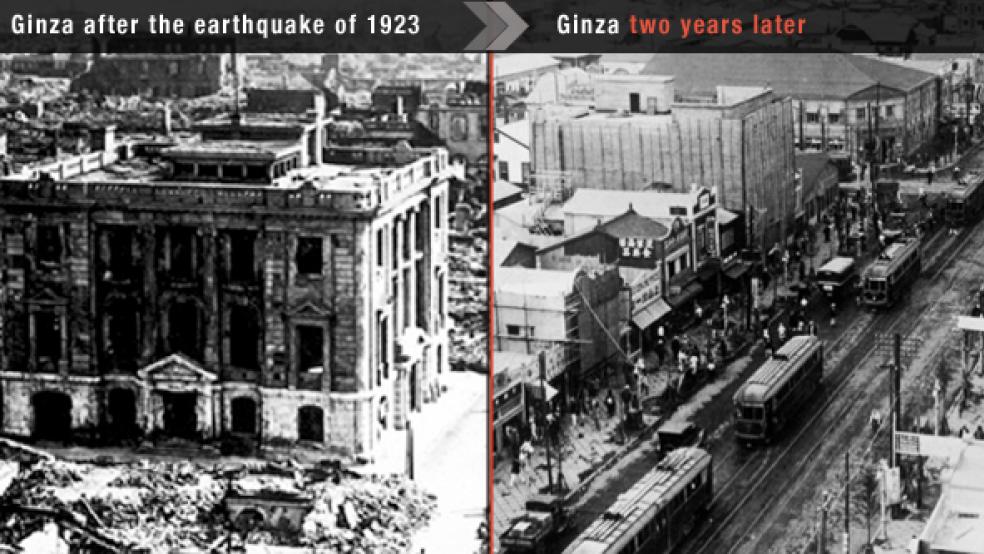

Alexander makes some interesting arguments when comparing the 2011 earthquake with the one in Kobe in 1995 and the famous Tokyo quake of 1923. In each of the earlier cases, the economy fully rebounded and then exceeded the pre-quake growth rate within two years. (And both quakes occurred in vastly more developed industrial zones.) Alexander points to before-and-after pictures of Ginza, the fashionable Tokyo district, in the 1920s: The quake leveled it, and there it was in 1925, bustling as it had been before the disaster, not a tram line out of place.