|

Only 69 shopping days until Christmas, which means it’s make-or-break time for retailers. Holiday sales account for about 20 percent of annual revenues—up to 40 percent for some stores—and an even larger share of profits. Retailers have their fingers crossed that households will be generous enough to assure a bright holiday buying season. So far, most signs suggest consumers are ready to spend, but analysts are divided over just how big their contribution will be.

Households far exceeded last year’s modest expectations. However, last year about this time the trends in consumer confidence, the stock market, and especially household incomes were all headed up; this year they are all headed down. The National Retail Federation forecasts a 2.8 percent gain in holiday sales this year, a bit higher than last year’s 2.3 percent projection. As it turned out, sales last year soared 5.2 percent, a five-year high. Some economists are optimistic that consumers will once again beat expectations. “We are looking for at least a 4.5 percent gain on a year-to-year basis,” says Mark Vitner at Wells Fargo Securities.

Households still face some strong headwinds. NFR chief economic Jack Kleinhenz says that persistently high unemployment stock-market gyrations, modest income growth, and rising consumer prices are all combining to weigh on holiday spending. “How Americans react to shaky economic data is the question,” he says, “but the good news for retailers is that shoppers have not yet thrown in the towel.”

That much was clear from last Friday’s report from the Commerce Dept. on September retail sales. Store receipts posted a solid 1.1 percent advance from August, and sales in both July and August were revised higher. The numbers relieve worries that households have not succumbed to the summer’s litany of bad news. Importantly, the September rise was broad, showing solid gains in necessities, such as gasoline, as well as in more discretionary areas, including cars, furniture, clothing, and restaurants.

to be gaining momentum

in the second half, not

sliding into a recession.

The jump in car buying last month, perhaps the most discretionary purchase for most households, is a particularly positive sign heading into the holidays. It suggests that the sales drop-off earlier this year was heavily influenced by supply disruptions following the Japanese earthquake. Sales rose to a 13.1-million annual rate, up sharply from 12.1 million in August, and close to the 13-million pace in the first quarter, before the earthquake. Economists at J.P. Morgan say the pickup in a big-ticket item like autos shows that consumers were willing to spend even amid tumbling confidence and stock prices.

Thanks to consumers, who weigh in at about 70 percent of GDP, the overall economy appears to be gaining momentum in the second half, not sliding into a recession. When the Commerce Dept. makes its initial report on third-quarter GDP growth on Oct. 27, economists now expect consumer spending to have made a positive contribution, growing at about a 2 percent annual rate. That would be faster than the second quarter’s weak 0.7 percent advance and a hopeful sign for retailers in coming weeks that consumers don’t always behave the way they say they feel.

However, a look at how consumers have managed to boost their third-quarter spending raises some questions. Households have been dipping into their savings at a time when their income growth has been weakening. In July and August, savings as a percent of after-tax income shrank from 5.3 percent to 4.5 percent, the lowest saving rate since December 2009, even as inflation-adjusted income fell in both months. Amid continued high uncertainty about job prospects, stock prices, and home values, it may be asking too much of consumers to depend increasingly on their savings to boost spending without help from stronger income growth.

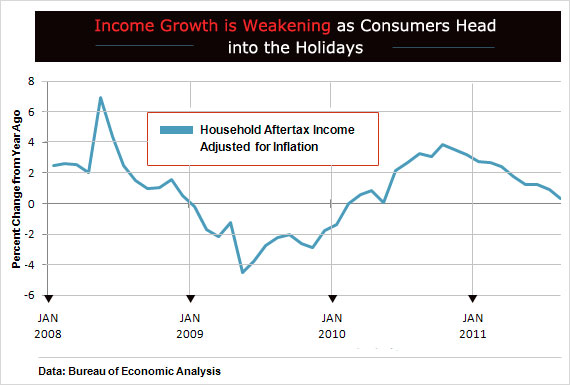

Income growth is the most important difference between last year’s holiday season and this year’s version. This time last year household income, after taxes and adjusted for inflation, was up 3.3 percent from 12 months earlier. This year the pace has slowed to only 0.3 percent. Stubbornly high fuel prices, which have eaten into the buying power of incomes, are a big reason, but the chief problem has been weak job markets. Since May, labor income from wages and salaries has risen at an annual rate of less than 1 percent, way below the 2.6 percent pace inflation during the same period.

say they will be looking for

discounts this year, stores are

planning strong promotions.

More important, survey measures show that households’ expectations for gains in real—or inflation-adjusted—income are historically low, says J.P. Morgan economist Michael Feroli. His analysis shows that expected real income growth outperforms many other popular guideposts in forecasting consumer spending, including current income, consumer sentiment, stock prices, and others. “If you had to pick one variable to predict real consumption growth over the coming year,”” he says, “it would be hard to do better than expected real income growth.” That’s a conclusion that should give retailers agita.

Given the pressures, consumers will be looking hard at price tags. The Accenture Holiday Shopping Survey says that nearly three-fourth of consumers describe their 2011 holiday spending as “careful” or “controlled," and 88 percent plan to spend the same or less than they did last year, up slightly from 83 percent in 2010. Accenture’s survey also shows that 93 percent of shoppers say they will be looking for discounts this year.

Stores are planning strong promotions, says NRF President Matthew Shay, but they are keeping their inventories lean in hopes of avoiding the margin-sapping deep discounting that has often been necessary to move overstocked items.

Ultimately, the success of this year’s holiday buying season may come down to jobs. Economists at Barclays Capital are modestly upbeat about consumer spending prospects, but they still believe that heightened uncertainty, stemming partly from the unknowns surrounding Europe’s debt crisis and U.S. fiscal policy, continues to stymie new hiring. Last year at this time, job-market conditions appeared to be improving. This year, households aren’t so sure.