|

Is the profits party over? Earnings during 2011, while solid, have slowed sharply from the heady gains in 2010, and many companies are warning investors that their fourth-quarter results will fall short of market expectations. The global slowdown is part of the story. However, the more moderate pace of profits, combined with the recent pickup in job growth, suggests a more fundamental turn in the earnings outlook for 2012. Clearly, the party is winding down, but in a way that will allow American workers to share a little of the fun.

One of the great anomalies in this recovery has been the exceptional strength in corporate profits in relation to the weak recoveries in economic growth and household income. While profits have boomed, labor’s share of national income has shrunk to a record low, as companies boosted productivity and slashed costs by shedding nearly 9 million workers. Now, companies appear to have reached the limit on the productivity gains they can achieve from their existing payrolls. They need more workers to meet demand, which is starting to push up costs and squeeze margins.

Companies begin reporting their fourth-quarter earnings in only a few weeks, and the early signals suggest much softer results. Dupont, Texas Instruments, Intel, and other high-profile multinationals have issued a rash of earnings warnings in recent weeks. Through Dec. 16, 93 of the companies in the Standard & Poor’s 500 stock index have announced shortfalls, compared with 25 companies that expect to beat expectations. By Thomson Reuter’s accounting, the 3.7 ratio of negative to positive surprises is far above the long-term average of 2.3 and matches the high reached during the 2001 recession.

Estimates in all 10 major S&P 500 sectors have fallen. Projections for the materials sector have come down sharply, reflecting weaker commodity prices, as have expectations for financials, which have suffered from lackluster trading volumes. Downgrades in the telecom sector have also been sharp. Fourth-quarter earnings for the S&P 500 are now expected to post a gain of 9.3 percent, down from 15 percent projected at the start of the quarter and from 17.6 percent expected in July.

The global slowdown outside the U.S. is one reason for the spate of downgrades. Overseas earnings account for more than 20% of U.S. corporate profits and an even larger share of the earnings of the S&P 500. Europe is heading into a recession, and growth has slowed in several emerging-market economies, such as China, India and Brazil, that had been key supports under U.S. exports. That weakness will extend into early next year. Projections of S&P 500 earnings growth in the first quarter of 2012 currently stand at 5.9 percent, says Thomson Reuters.

Earnings for the full year in 2012 may not perform much better than the first-quarter expectation. The increased reliance on demand from emerging markets and the healthy condition of corporate balance sheets were two trends that helped support profits during the recession. “Both of these factors have run their course,” says Equity Strategist Barry Knapp at Barclays Capital. Knapp expects the fourth-quarter results to point the way to earnings growth for the S&P 500 in the mid-single digits for 2012.

But the more important story for profits in 2012 will be the downshift in productivity, which almost always goes hand-in-hand with the ups and downs in a company’s bottom line. The big productivity gains, which companies had attained in the recovery’s early going and which had provided the greatest support under profits, are fading. Those gains were not the lasting kind that comes with new technology or higher skill levels. Meeting the slump in demand during the recession with steep payroll cuts provided only a short-term boost to productivity growth. Now, with payrolls unusually thin amid growing demand, businesses need to pick up the pace of hiring.

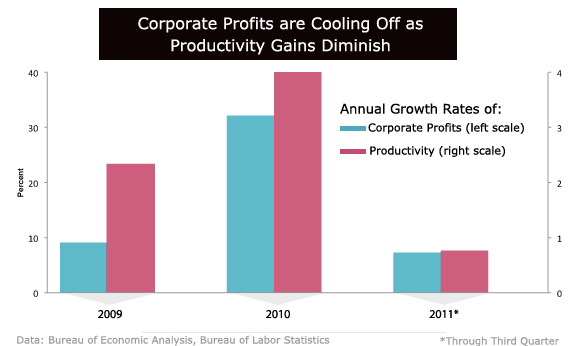

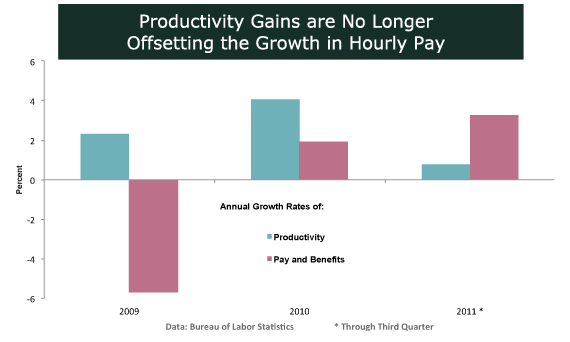

So far this year, productivity—measured as output per hour worked in the nonfarm business sector—has increased only 0.8 percent from the year before, down sharply from the 4.1 percent pace in 2010. At the same time, profits are up 7.2 percent vs. the 32 percent surge in 2010, based on the Commerce Dept.’s broadest measure. Profits are cooling off, in large part, because productivity gains are no longer offsetting the rise in worker’s pay and benefits. That means unit labor costs are now rising, after falling in both 2009 and 2010, making it more expensive for a company to produce each one of its products.

The labor markets are far from strong, but they are taking a turn for the better, and wages and benefits are slowly picking up. Private-sector job growth has accelerated, to 160,000 per month in the three months through November, and the unemployment rate fell to 8.6 percent in November. Weekly jobless claims, which tend to foreshadow the trend in payrolls, tumbled to a new post-recession low in mid-December, strongly suggesting that the labor market is shifting into a higher gear. Economists at UBS believe recent job gains may even be understated, given indications of stronger hiring at small businesses, improved consumer assessments of labor markets, and the speedup in consumer spending.

If the current pace of job growth continues in 2012, as most economists expect outside of a financial meltdown in Europe or a fiscal blowup in Washington, the combination of slower productivity growth and faster pay growth will continue to put upward pressure on the cost of doing business. Labor compensation, comprised of both pay and benefits, is hardly robust, but so far this year companies have lifted workers’ compensation by 3.2 percent from the 2010 average. In 2010 pay and benefits increased only 1.9 percent, and in 2009 they fell 5.7 percent. Not surprisingly, in the fourth quarter of 2009 the growth in corporate profits peaked at 62 percent, based on Commerce Dept. data.

For calendar year 2012, analysts are projecting earnings for the S&P 500 companies to rise 10 percent, according to Thomson Reuters, but after companies have reported this quarter and next, that forecast is bound to look a little too optimistic. The good news for the economy, however, may well be that the loss to the corporate bottom line will be a gain for the U.S. workforce.