PARIS — The young men who checked into the rental house in Bobigny before the Paris attacks were well-mannered and well-dressed. In town for business, they said. The men paid 100 euros a night for the two-story brick house in the middle-class Paris suburb. When they arrived, one of them presented the house’s owner, who lived on the same quiet street, with his ID card: Brahim Abdeslam.

Three days later, Abdeslam lay dying on the floor of a Paris cafe, a coil of multicolored wires visible under his T-shirt, just moments after he detonated his suicide vest. Abdeslam would now be known as one of the perpetrators of the worst attacks on French soil since World War II, an offensive that laid bare the Islamic State’s power to strike the heart of Europe.

Investigators are still piecing together how a group of at least nine young men, believed to be mostly French and Belgian nationals who became radicalized in Europe, planned their offensive, funded it, equipped themselves with explosives and assault rifles, arranged safe houses and launched the coordinated attacks, which killed 130 and injured more than 350 across Paris.

European authorities, combing through electronic and banking records and questioning dozens of people detained in raids over the past week, don’t yet know how long the men, many of whom are known to have traveled to Syria to fight with the Islamic State, spent preparing the attack.

But information gleaned about the days leading up to Nov. 13 provides clues about how the men crafted a carefully orchestrated assault that European and American officials say suggests training and perhaps oversight and direction from Islamic State operatives in their base in Syria and Iraq.

“For such an attack, involving so many people, it must have been decided near the highest level,” said Claude Moniquet, a former French intelligence official who heads the European Strategic Intelligence and Security Center. The Islamic State’s military operation, whose senior leaders include numerous former military officials from Iraq, “would never let someone below them direct a strategic operation.”

[What we know about the Paris attacks and the hunt for the attackers]

The roots of the attacks — which struck France’s largest stadium, a crowded concert hall, and a series of restaurants and cafes — may be visible in the suspects’ path to radicalization.

While their stories vary — one had been a student, another a bus driver, another a bar owner — many came from Muslim families that were neither fundamentalist nor extreme. Their radicalization appears to have happened over just the past few years, or even a couple of months.

At the center of the plot appears to have been Abdelhamid Abaaoud, a 28-year-old Belgian of Moroccan descent. While Abaaoud was not one of the men first identified in the Nov. 13 assaults, officials say he was the cell’s most senior member, possibly tasked by Islamic State superiors to coordinate the attacks. Police say Abaaoud also handled one of three Kalashnikov assault rifles found in an abandoned car after the attack, suggesting that he may have helped both plan and carry out the violence.

He died Wednesday during a police raid on an apartment in Saint-Denis, just outside Paris, where others said to be plotting a follow-up attack were hiding.

Abaaoud, who even before the attacks had become a well-known figure in Islamic State propaganda, had ties to some of the other attackers, including Abdeslam. Abaaoud served time in a Belgian prison with Abdeslam’s brother, Salah, who is still on the run.

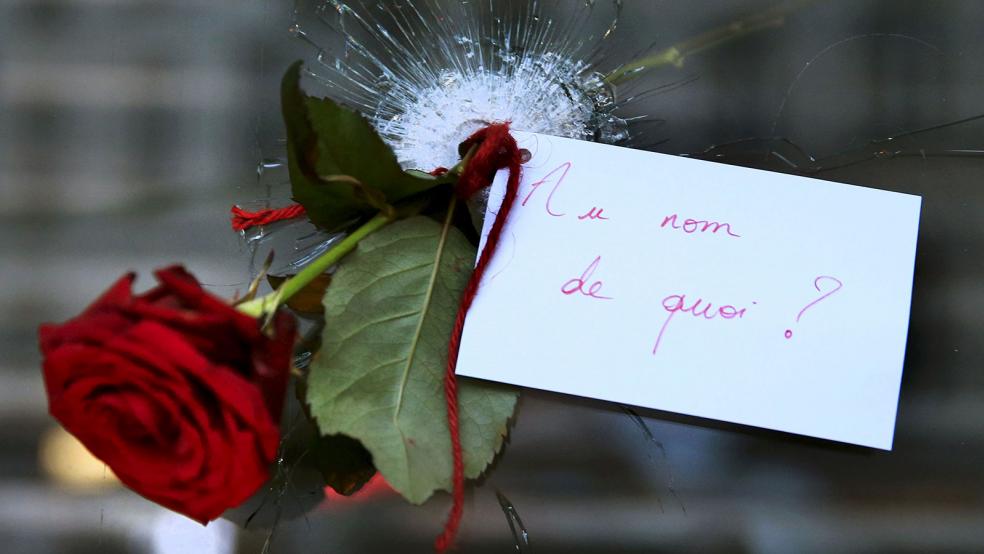

France mourns after the deadly attacks in Paris

At least 130 are dead in a coordinated terrorist assault across the French capital.

Abaaoud was a resident of Molenbeek, a hardscrabble Brussels neighborhood known as a breeding ground for extremism. According to Belgian officials, 48 of the 141 Brussels residents known to have gone to Syria to fight in 2013 or 2014 came from Molenbeek.

“All these guys know each other, and when someone is going to Syria, others think about going,” said Montasser AlDe’emeh, a researcher on Islamic extremism who runs a center to discourage young Muslim Belgians from going to Syria. “In a few years, these guys who didn’t know how to pray are coming back in and, in one, two, three years, they are the most wanted people in Belgium.”

Abaaoud is said to have first gone to Syria in 2013 and joined the Islamic State. French officials don’t yet know when or how he returned to Europe prior to the attacks.

In August of this year, an Islamic State supporter detained when he returned to France from Syria told French authorities that Abaaoud had, in Syria, instructed him to strike sites crowded with people. The man, Reda Hame, said he had been given several targets in France, including “concert halls” and “food markets.”

[France confirms death of Paris attacks’ alleged ringleader]

Like Abaaoud, most of the suspected attackers were already known to European authorities, some for suspected support for militants, others for ordinary crime.

One of them, Samy Amimour, a 28-year-old from the Paris suburb of Drancy, had been arrested in 2012 while trying to travel to Yemen to fight. His family said he spoke no Arabic at the time and had only recently begun to watch extremist preachers on the Internet and urge his mother to wear headscarves.

In 2013, Amimour violated his court supervision and left France for Syria, causing police to issue an international arrest warrant for him. Amimour’s father flew to Syria to persuade him to come home in 2014 but returned to Drancy alone. Amimour died in the Bataclan concert hall, where he and two other attackers killed nearly 90 people.

Bilal Hadfi, who at 20 was the youngest of the known plotters, had been monitored by the Belgian government beginning after the January attacks in Paris on the satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo and a kosher supermarket. A Paris native who later lived in the Brussels neighborhood of Molenbeek, Hadfi expressed support during a class at his school for the massacre, which killed 17 people.

Sara Stacino, one of Bilal’s teachers, alerted the school administrators in writing. “But we all took a rather cautious stand,” she told VRT television.

Soon afterward, Belgian authorities began to track Hadfi’s movements, according to the Justice Ministry. Around the same time, his behavior changed. “He stopped smoking cigarettes and hash, but I saw this as a good change,” said his mother, Fatima, according to the La Libre Belgique newspaper. “I didn’t see it coming.”

Around Feb. 15, Hadfi told his mother he was going to Morocco to visit his father’s grave. The night before he left, he said goodbye to his mother.

“He came home with his eyes red. He took me in his arms. He knew that this was a departure without a return,” his mother told the newspaper in November, before the attacks took place.

Hadfi began the long trip to Syria. Once there, he used an alias on Twitter to threaten the West. “They should no longer feel safe,” he wrote, “not even in their dreams.”

In March, Belgian police alerted to Hadfi’s presence in Syria raided the family home. “He is a ticking time bomb,” Hadfi’s mother told La Libre Belgique. “I had the feeling he could explode at any time.”

A few months later, in August, Belgian police raided a cafe-bar in Molenbeek. Authorities had received complaints about the smell of cannabis at Café Les Béguines, owned by Brahim and Salah Abdeslam and other family members. Police found “butts of joints in the ashtrays” and “remnants of hallucinogens in possession of customers.”

After the attacks, a young man who lives near Café Les Béguines told RTBF television that a week before the Paris attacks Brahim Abdeslam had asked him to stash some Kalashnikovs.

“We asked him, ‘This is nonsense, right?’ ” said the man, who did not give his name. Not at all, Abaaoud replied, according to the man’s accounts. “ ‘I have enough stuff to blow up Belgium.’ ”

[Paris attacks underscore risks of a slow U.S. campaign against Islamic State]

Authorities are still working to determine the identities of the remaining attackers, including two who appear to have entered Europe on a migrant trail through Greece. They are interrogating additional suspects thought to have been connected to the attacks.

Investigators say the attackers arrived in France one to three days before the assaults, installing themselves in safe houses on the outskirts of Paris. In addition to the Bobigny house and the Saint-Denis apartment, Salah Abdeslam booked two rooms at a hotel-residence in Alfortville, a river port outside Paris.

French officials say they don’t yet know whether the men used the safe houses to assemble the explosives used in the attacks.

Several of their suicide vests did not detonate effectively, suggesting the cell’s bomb-making skills were crude. At Cafe Comptoir Voltaire, one of the sites targeted, Brahim Abdeslam killed only himself when he detonated his vest. Across the city, Hadfi, apparently unable to get into the stadium, appears to have blown himself up at a nearby McDonald’s; no one else died.

Authorities are not certain where the men obtained their automatic rifles. They suspect they came from Belgium, where the prime minister is seeking tighter gun controls.

In the Paris suburb of Bobigny, residents said they heard no noise or disturbances in the days before the attacks from the house used by Brahim Abdeslam and his fellow plotters.

Several people on the block did see two rental cars used in the attacks — a Volkswagen and a SEAT — parked in front of the property, a narrow, well-kept house tucked between other single-family homes.

After the attacks, French authorities reconstructed the vehicles’ movements using the cars’ GPS devices.

The black SEAT was used to conduct a series of attacks in which the perpetrators sprayed gunfire into crowds at Le Carillon, La Belle Equipe and other popular establishments in Paris’s 10th and 11th districts. At least 40 people were killed, many of them sitting outdoors on a mild November evening.

At the empty Bobigny house after the attacks, French authorities found only a few mobile phones and SIM cards. The attackers had left behind few clues when they set out for Paris and the mayhem that followed.

This piece was originally published in The Washington Post. Booth reported from Brussels. Souad Mekhennet, Cléophée Demoustier and Virgile Demoustier in Paris and Annabel Van den Berge and Steven Mufson in Brussels contributed to this report.

Read more at The Post: