Is the federal income tax code fair? As Americans put away their tax forms for another year, statistics indicating that the top 5 percent of the nation’s taxpayers pay 60 percent of federal income taxes seem to confirm that our graduated income tax system does what it says it does: demands the most from those most able to pay.

But fairness is often in the eye of the beholder. A proliferation of tax breaks, often aimed at making the tax system more equitable, has led to some stunning disparities in how Americans with similar incomes are taxed. As the deficit shines a light on the need for more revenues, tax breaks, worthy and wacky alike are coming under increasing scrutiny.

Consider this tale of two taxpayers.

Melissa Lopez, 20, and Jessica Hummel, 23, have almost identical household incomes, but their federal income tax bills are vastly different. Both of the single Southern California women secured their first “real” jobs last summer, earning fairly paltry wages of $9,000 and $10,000 respectively. Neither owed federal income taxes. In fact, they both received subsidy payments through the tax code.

But that’s where the similarities end. Hummel’s subsidy was $300. The subsidy Lopez received was more than 14 times more --$4,400 to be exact, in part because she had a baby last year.

There are hundreds of little provisions in the U.S. tax code that favor some taxpayers and penalize others, creating vast gulfs between taxes paid by people with similar wealth as the rule rather than the exception. To be sure, the tax code has always given some preferences to those engaging in activities considered beneficial for society, from having kids to buying homes. But over the past decade so-called “targeted” tax breaks have burgeoned, often without careful scrutiny. That’s got many experts saying that the system has become increasingly complex, inequitable, often bizarre and desperately in need of reform.

“Americans spend too much time looking up and down the income scale for unfairness, when they really ought to be looking sideways,” said Pete Sepp, vice president of policy and communications for the National Taxpayers Union. “When you are able to directly compare your own income with that of another person and see how different the tax bill is, it destroys any confidence that the system is fair and comprehensible.”

The Fiscal Times asked the Santa Monica accounting firm of Holthouse Carlin & Van Trigt to examine a half-dozen hypothetical situations to see how much the tax bills of people with identical incomes can vary. The results: In every case, one variable would create a tax swing of 100 percent or more. And that doesn’t include such variables as state and local income taxes and property taxes paid by homeowners.

• The guy earning $50,000 annually who bought a golf cart, for example, paid $5,000 less in federal income tax than the guy who bought a car instead.

• The retiree who received the bulk of her income from a teacher’s pension paid nearly three times more than the retiree whose $40,000 in income came partly from Social Security.

• Buying a home in 2009 could net you a $10,000 tax advantage over a renter.

• And earning a high income from wages versus investments meant you paid twice as much in income tax.

“These tax provisions have accumulated often for what seemed to be good reasons at the time, but they can be quite remarkably unfair if your idea of fairness is that people of the same income should pay the same,” said Alice Rivlin, economist and senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. “In their totality, they make the tax system much more complicated, much less efficient and much less equitable.”

Indeed, tax breaks aimed at encouraging certain activities — like home ownership and going “green” — have proliferated to such a degree that the Tax Foundation, a Washington, D.C., think tank, recently published “naughty” and “nice” tax forms as an April Fool’s joke. The funniest part, for those in the know, was that all of the tax credits and deductions on the forms were real.

But Evelyn McLean-Cowan finds the real tax system arbitrary and not a bit funny. The Wisconsin-based graphic designer is struggling to pay bills for her two college-age children while still reeling from the 2008 floods that consumed the family’s basement and recreation room.

She was delighted to hear that a special federal tax credit provides a huge break — up to $4,000 — to people who send their kids to college in this same flood zone, thinking that it might help her replace the ruined carpets and furniture. But her delight turned to anger when she realized she didn’t qualify. Why? The credit pays parents who send their kids to formerly-flooded colleges, not parents who are struggling with college bills and flood expenses at the same time.

In other words, a California parent with no flood damage could claim this flood-related break by sending her child to the University of Wisconsin (long after the flood waters receded). But McLean-Cowan can’t claim it because her college student comes home to once-flooded Fond du Lac from studying in Chicago.

“Why should parents benefit from the flood when they weren’t even affected?” she asks. “If this is supposed to be helping flood victims, why isn’t it helping the people who are actually dealing with flood expenses?”

McLean-Cowan also bought an energy-efficient water heater to replace the one that was damaged in the flood. New tax credits could have reimbursed her for 30 percent of the cost of the water heater, but she bought it four months too soon. The tax credit for “energy property” went into effect in February of 2009 and she replaced her water heater in November of 2008.

Notably, energy credits can be used to defray the cost of solar heating panels and replacing water heaters, air conditioners or furnaces, but not to buy a new energy-efficient refrigerator.

“It’s become a spoils game,” said Philip J. Holthouse, partner at Holthouse Carlin & Van Trigt. “Whoever has the most effective lobbyist gets tons of goodies.”

“Tax cuts” that support social aims, like encouraging clean energy, have the support of both parties. Democrats see them as social spending programs, while Republicans support anything that allows taxpayers to keep more money in their own pockets. That often means that they don’t receive the appropriate level of scrutiny, said Clint Stretch, director of tax policy with Deloitte & Touche.

“If you went to Congress and said that you wanted them to appropriate $37 billion so that people could buy high-efficiency widgets, they would ask if you were out of your mind,” said Stretch. “But the magic of tax credits is that they’re so easy to approve.”

When asked how to fix a tax system burdened with complex breaks and inequitable treatment of taxpayers, virtually everyone repeats the same message: In 1986, then President Ronald Reagan ushered through a tax reform measure that eliminated most tax shelters in exchange for lower rates for everyone. Something similar is needed now, the experts concur.

And yet, Stretch notes, Congress continues to move in the opposite direction and is now debating a half-dozen laws, including a “green jobs” bill that could make the problem worse.

“The system is beginning to sag under the weight of its own complexity,” said Patrick Fleenor, chief economist at the Tax Foundation, and an advocate for reform. “There will be a breaking point where not even computer software and an army of accountants can keep up with it.”

Taxpayer tales: *

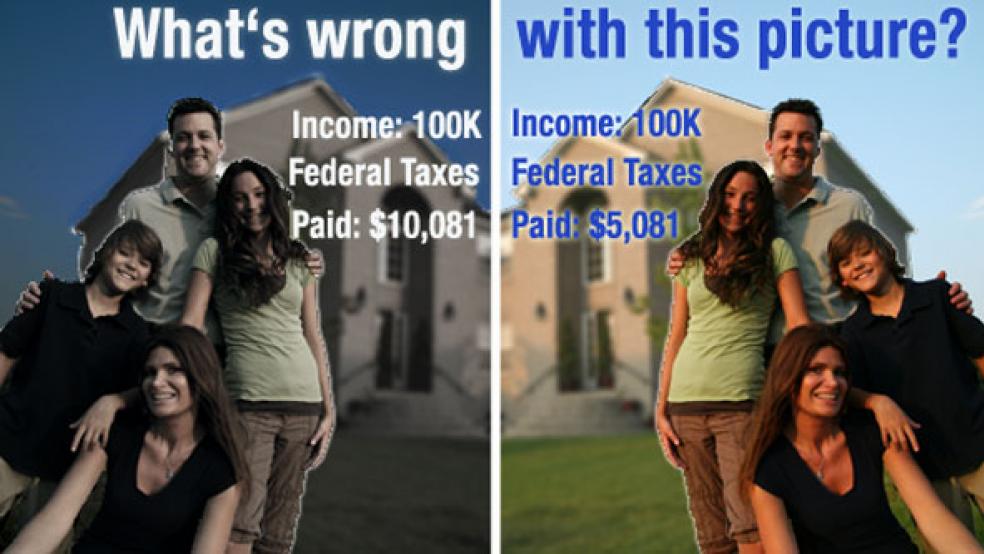

Scenario #1: Family of four made up of renters, earning $100,000, with 2 children, ages 18 and 20.

• Family #1 sends both kids to college, paying $5,000 each toward their expenses which qualify them for tax credits of $2,500 per child. Their federal income tax: $5,081

• Family #2 has both kids living at home. Their federal income tax: $10,081.

Scenario #2: Single individual, earning $80,000.

• Individual #1 rents an apartment and doesn’t itemize deductions. Federal income tax: $13,519

• Individual #2 buys a home in mid-2009, using the first-time homebuyer tax credit and itemizing deductions, which also gives him the ability to write off mortgage interest, property taxes and claim his charitable contributions of $500. Federal income tax: $3,781.

Scenario #3: Single renter, earning $50,000 in wages

• Individual #1 buys a car to get to work. Because he has no other itemized deductions, he can’t claim a benefit for the new automotive sales tax deduction. His federal income tax: $5,956

Individual #2 buys a street-legal golf cart to get around his small town. Golf carts were among electric vehicles that were the recipients of some of the most lucrative 2009 credits, ranging from $3,500 to $7,000. His federal income tax: $537

Scenario #4: Single renter earning $60,000 annually

• Individual #1 works as an employee, but has $15,000 in unreimbursed business expenses. Some of these expenses can’t be written off, but will cause him to itemize deductions. Federal tax: $6,144.

• Individual #2 is self-employed and claims $15,000 in business expenses, which reduce his taxable income. Federal income tax: $4,454.

Scenario #5: Retiree, with $40,000 in income.

• Individual #1 receives half f his income from a pension and half from Social Security, which is not taxable unless you earn more than a set amount. Federal income tax: $1,559

• Individual #2 receives all her income from a teacher’s pension, which is fully taxable. Federal income tax: $3,934

Scenario #6: Single woman with $250,000 in income

• Individual #1 earns the $250,000 from her job as a lawyer. Federal income tax: $63,049

• Individual #2 gets the $250,000 from $125,000 in ordinary dividends; $75,000 from interest; $75,000 from qualified dividends (taxed at lower rates); and $50,000 from tax-exempt interest. Federal income tax: $37,296.

*All examples are for federal income tax for the 2009 tax year. Compiled by the Santa Monica accounting firm of Holthouse Carlin & Van Trigt.