Employers' spending on health coverage for workers spiked abruptly this year, with the average cost of a family plan rising by 9 percent, triple the growth seen in 2010.

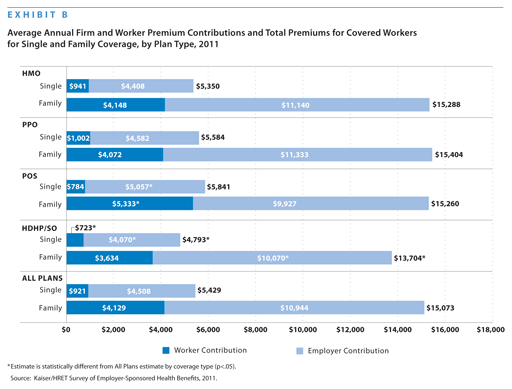

Family plan premiums hit $15,073 on average, while coverage for single employees grew 8 percent to $5,429, according to a survey released Tuesday by the Kaiser Family Foundation and the Health Research & Educational Trust. (KHN is an editorially-independent program of the foundation.)

Workers paid an average of $921 toward the premium of single coverage and $4,129 for family plans.

The results mark a sharp departure from 2010, when the same survey found average family premiums up only 3 percent.

Although many benefit analysts say the federal health law’s requirements played only a small part in the rise, the results could provide political fodder for both supporters and opponents of the law.

"It's problematic," says Democratic pollster Celinda Lake, because the No. 1 concern cited about the health law is a fear that it will increase costs. Still, Lake notes that many Americans don't know much about the law, so the news of rising premiums "could also fuel support for provisions in the law that require insurance premiums of 10 percent or more to be reviewed."

Premium increases have played a starring role throughout the debate over the health care law.

Before the law's passage in 2010, for example, insurer WellPoint's effort to raise rates by as much as 39 percent for some of its California customers drew sharp rebukes from the Obama administration and helped build support for the law in Congress.

Proponents of the law also point to this spring's decision by Aetna to lower premiums for individual policies in Connecticut as an effect of the health law.

But opponents say the law adds costly new mandates – and has not shown results yet.

"Despite the president's repeated promises that the Democrats health care law would lower the cost of health insurance, employers are still facing higher health costs," said Ways and Means Health Subcommittee Chairman Wally Herger, R-Calif., in a written statement Friday.

Many factors drive premium growth, the main one being actual spending on medical care, including jumps in prices charged by hospitals and doctors and growing use of expensive new drugs and technologies. State regulators have widely varying authority over premium increases for policies sold to individuals and small businesses. Currently, 26 states and the District of Columbia have the authority to veto rates deemed excessive for at least some types of health insurance. Additionally, seven states have the power to review rate increases in advance but not to block them.

Over the past decade, premiums have risen steadily, with double-digit increases seen from 2000-2004, the Kaiser survey and other tracking reports show. Growth in premiums moderated starting in 2006, averaging about 5 percent for several years, the survey found.

The benefits firm Mercer reported earlier this year that per-worker health spending by employers rose at about 6 percent annually for about the past five years, rising to nearly 7 percent last year. Projecting future increases is harder, as many surveys estimate based on initial negotiations between insurers and employers, before changes to benefits are made to slow premium costs. In a study out last week, Mercer projected that employers may see their health spending rise 5.4 percent next year, while a similar survey released in May by accounting firm PwC estimated an 8.5 percent rise next year.

Insurers often set rates well before they go into effect, using data to estimate coming expenses, including how much policyholders are expected to use medical services. Analysts have noted a slowdown in doctor office visits, births and elective surgeries they say is related to the economy.

One factor in this year's increases was that "employers and insurers expected a faster economic recovery and geared premiums to higher levels of utilization," says Drew Altman, president and CEO of the Kaiser Foundation.

The growth of premiums far outpaced the growth in workers' wages – as it has for the past decade. Wages grew by 2 percent this year.

Although premiums rose, employers kept the percentage of the premium workers pay about the same: An average of 18 percent for single coverage and 28 percent for family plans. Still, with rising costs, workers paid more, up an average of $132 a year for family coverage. Since 1999, the dollar amount workers contribute toward premiums nationally has grown 168 percent, while their wages have grown by 50 percent, according to the survey.

The results from Tuesday's survey were drawn from the responses of more than 2,000 large and small businesses. The survey was done from January to May – well before the September start date of a rule requiring states to scrutinize rate increases of 10 percent or more for policies sold to individuals and small businesses.

Other provisions of the federal law were in effect, including those that allow parents to keep their children on their coverage until age 26, a ban on lifetime benefit limits and a requirement that preventive services, such as some cancer screenings, be offered without co-payments. Insurers are also barred in most cases from canceling policies of those who fall sick.

Altman said the foundation's research found that current rules in effect "could only have had a modest impact on premiums,” accounting for about 1.5 to 2 percentage points of the 9 percent increase. Other surveys, including a government analysis, also estimated the early rules’ effect on premiums in a similar range.

Michael Thompson, a principal at PwC, said his work with employers found that the new provisions had a negligible effect on premium costs, often because employers were already making benefit changes that shifted more costs to workers in order to slow premium growth.

The one provision of the new law that "had an almost universal impact" on employers was the one allowing parents to keep their adult children on their policies, Thompson said, although "interestingly it didn't necessarily raise their per-head cost (because young people don't cost as much to insure)."

Based on employer responses, the Kaiser survey estimated that employers added 2.3 million young adults to their coverage. Last week, the government’s National Center for Health Statistics found that the number of uninsured people ages 19 to 25 dropped by almost 1 million in the first three months of this year.

Premiums – and increases – vary widely around the country. Average increases for small businesses in Maine, for example, rose 17 percent this year, according to state data. Regulators in Oregon, meanwhile, approved small business increases ranging from zero to 15.6 percent, depending on the insurer. This month, Kaiser Permanente in California told 360,000 small businesses that it would reduce their already-in-effect increases by 1.2 percent immediately, following discussions with regulators. (KHN is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.)

Marge Kraskouskas, vice president of human resources for the Hockomock Area YMCA in North Attleboro, Mass, says ten years ago, family coverage cost her firm $567 a month; now it’s $1,455.

Her rates rose 7 percent this year, "one of the lowest increases in years," she said. "Still, I don't care if you're talking 7 percent or 13 percent, it's a killer in the budget."