Pity the college graduate, burdened with shocking levels of student-loan debt and looking for a job in the worst employment market in two decades.

But save a little pity for the rest of us.

The staggering amount of outstanding student debt — nearly $1 trillion owed – is beginning to impede the U.S. economy as a whole, a new report from the New York Federal Reserve suggests, chiefly by robbing the housing market of its richest crop of new buyers: young college graduates.

RELATED: Students Are Fleeing Liberal Arts - How It Could Hurt the U.S.

The statistics in the report are dismaying in themselves. With the number of borrowers approaching 40 million nationally, including more than 40 percent of 25-year-olds, the average balance on their loans has risen to $25,000. About 6.7 million of all student borrowers, or 17 percent, are delinquent on their payments three months or more.

"Delinquent student loan borrowers have a very difficult time accessing credit and the share of those borrowers is greater today than in the past," said Donghoon Lee, a senior economist for the New York Fed and one of the authors of the report.

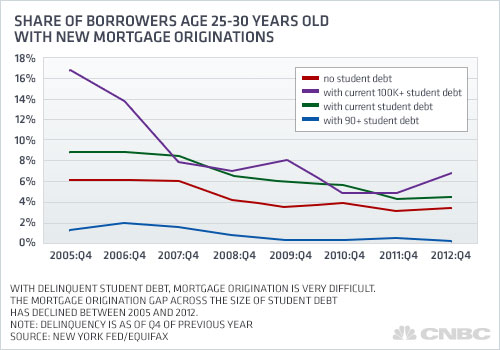

For the average homeowner, the worst news is that these overleveraged and defaulting young borrowers are no longer qualify for other kinds of loans — particularly home loans. In 2005, nearly nine percent of 25- to 30-year-olds with student debt were granted a mortgage. By late last year, that percentage, as an annual rate, was down to just above four percent.

The most precipitous drop was among those who owe $100,000 or more. New mortgages among these more deeply indebted borrowers have declined 10 percentage points, from above 16 percent in 2005 to a little more than 6 percent today.

"These are the people you'd expect to buy big houses," said student loan expert Heather Jarvis. "They owe a lot because they have a lot of education. They have been through professional and graduate schools, but their payments are so significant, they have trouble getting a mortgage. They have mortgage-sized loans already."

For years, economists and student advocates warned that the greater debt load would have an adverse impact on graduates' borrowing power. Now the statistical evidence is mounting. Last month, a Pew Research Center survey found that the share of millennials who own their homes had fallen from 40 percent to 34 percent during the recession, with a similar decline in residential debt.

Everyone has had a harder time qualifying for a mortgage since credit standards tightened in 2008, of course. And it could be that younger people suddenly prefer renting (or living at home). But by looking at mortgage originations, the New York Fed's report ties college graduates' lack of home ownership more directly to borrowing woes.

The implications for the housing market are serious. The number of first-time homebuyers, more than half of whom are aged 25 to 34, has been shrinking since the recession struck, and young buyers now make up their smallest share of the housing market in more than a decade.

In February, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau asked private lenders to suggest options for relief of student loan borrowers. "They are increasingly concerned about the effect of student debt on household formation to see if there's anything they can do to thaw the marketplace," said Mark Kantrowitz, publisher of the financial aid website Finaid.com.

But existing efforts to prevent delinquency on federally backed loans — such as basing the size of borrowers' payments on their income — have sometimes made getting a mortgage more difficult. "It confuses the mortgage process," said Jarvis. "Income-driven programs do help them afford a home and ought to make them more creditworthy, but they have not communicated well."

The best fix for everyone would be a faster growing economy, which would provide jobs and higher incomes to those who have borrowed. Until then, Jarvis sees the average college grads' situation as a Catch-22. "If you don't prioritize your student loan debt you won't be able to get credit in the future," she said, "and if you do pay it, you won't be able to afford anything else."

By Paul O'Donnell, CNBC

This piece originally appeared in CNBC.com