Forty-five years ago this July 20th, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first human beings to set foot on the moon. Their mission represented an emphatic American victory in the first space race, which began in earnest in 1957 when the Soviet Union launched a notably unattractive satellite, Sputnik, into orbit.

Since then, however, America’s national space program has essentially foundered. It improved space travel by building and then scrapping the Space Shuttle, without ever accomplishing – or attempting – a mission as bold or impactful as the one in 1969. It’s time for a new one. To win the next space race, the U.S. should announce its support for private property rights in space, and NASA should take a back seat.

Related: NASA Makes Coburn’s List for Wasteful Spending

To be fair, NASA’s not really at fault here: its business model is just wrong. In the national consciousness, NASA seems like a luxury, in the same low-priority bucket as the F-22A fighter and development aid for Bosnia. And unlike those other items, it’s not really clear what the last thirty years of NASA funding has given us. As America’s government-run space monopoly, NASA is a money hole, no more viable over the long run than is Amtrak.

That’s a shame, because we’re not far off from the next major iteration of space exploration. Tesla Motors and SpaceX CEO Elon Musk believes that humans could be travelling to Mars within 10-12 years. And former NASA official and Stanford astronautics professor G. Scott Hubbard sees private space exploration for tourism, residency, or resource extraction as goals for the next iteration of space travel.

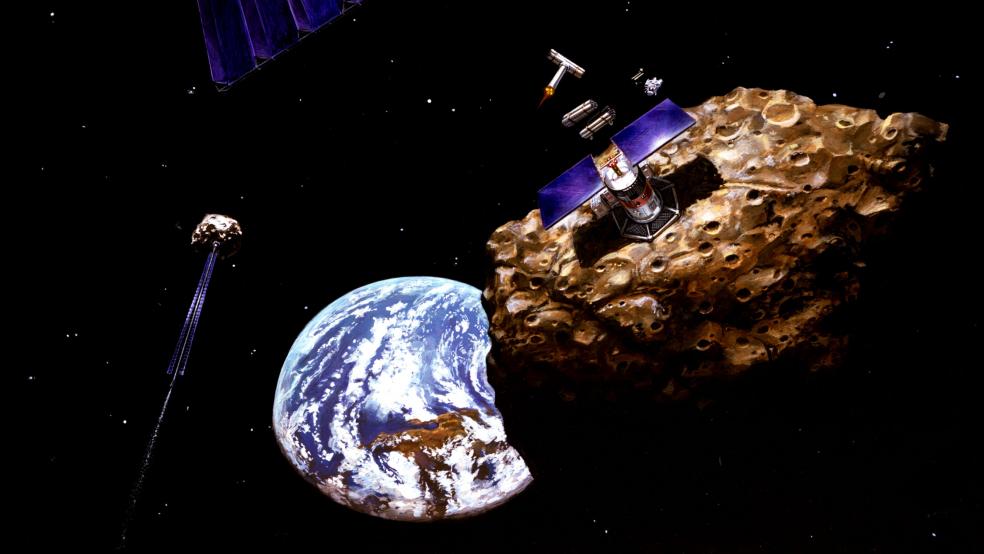

That’s the new space race: not tourism, not residency per se, but resource extraction.

According to some estimates, a single half-kilometer asteroid could contain over $20 trillion worth of metals and other resources.

The first nation that can import and tax the raw materials of bodies in our solar system would experience an economic boom unparalleled in generations, if ever.

In addition, the military-technological spillover advantages from a vastly expanded space industry might never be surpassed. Since space is infinite, there’s no limit to how far the mining sector can expand – the bounds of the solar system in the short term, but in the longer term, who knows? It would be a period of international growth and change unseen since the Age of Discovery, when Spain and Portugal broke out of the European system and became superpowers almost overnight. And, like the 1400’s, the first country up there will win.

But only private industry will risk it. Only the private sector has people willing to take losses for years, and often be ruined, for the chance to succeed beyond imagination.

Related: SpaceX Capsule Docks at Space Station, Opens New Era

The Obama administration’s 2010 space strategy, which encouraged commercial firms to develop the capability to fly U.S. astronauts into space, did recognize that private industry will be the driver of space exploration. The problem, however, is that human launch capability is not that intrinsically valuable a service.

True, we need it to put astronauts into the International Space Station, where they produce marginally valuable scientific research and watch the World Cup. But that still falls into the “expensive curiosity” label that killed the Space Shuttle. Even a human visit to Mars or a permanent human presence on the moon would not be much more than a milestone for the human race, which – though laudable – is not the most alluring incentive for government or private cash.

But what if space exploration companies could be offered property rights for the resources they extract as well? Private property rights are a mainstay of economic development theory. This would in one stroke encourage far-seeing corporations to invest in space development projects that are virtually guaranteed to have a long-term (indeed, almost infinite) reward.

Related: NASA Rover Drills Into Its First Martian Rock

One that’s already in the market is Planetary Resources, a new asteroid-mining company supported in part by Google’s CEOs Larry Page and Eric Schmidt. Given the right policy support, others would be quick to join it. Then it’s California in 1849, and the gold rush is on.

The U.S. should thus make an explicit promise to space entrepreneurs: If they pay U.S. taxes, follow to-be-created US environmental regulations, and share their technology with the government, the government will defend their claim diplomatically and legally. NASA in this model would play the role of a regulator and information repository, and possibly an R&D lab for US companies.

They’d need it, because other countries would be upset. Operating in the quirky netherworld of never-put-to-the-test space law, the U.S. would be essentially creating customary law on the fly. To smooth the transition, it could also offer a diplomatic incentive: that it would defend the claims of foreign companies whose countries recognize U.S. claims.

Related: Why This Billionaire Is Shooting for the Moon

That would be a powerful inducement to cooperate in the new space race. Most likely, after initial responses ranging from ridicule to Brazil-level meltdown, the most developed US allies like Japan, Germany, and the Anglosphere would follow suit, either alone or in alliances with companies from the developing world.

Because, if it works, everything else looks like pawn-grabbing. The frontiers of Ukraine, China’s claim to Pacific atolls, even the vast caldron of inchoate sectarian rage in the Middle East: strategically, all would have less of a long-term impact than the economic and technological benefits of space mining. The first countries to do it successfully will be the superpowers of the space age – and the last may disappear.

And if it goes nowhere, then so what? The U.S. has lost nothing except some diplomatic angst.

There’s always more where that came from.