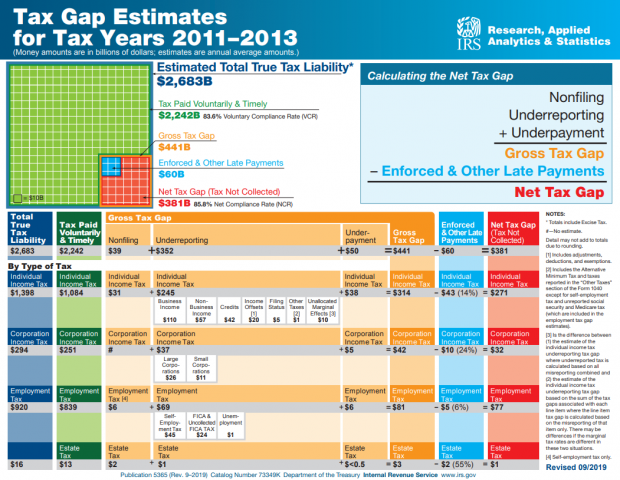

The Internal Revenue Service on Thursday said that the annual “tax gap,” the difference between federal taxes owed and the amount actually collected, averaged $441 billion from 2011 to 2013. Of that amount, an estimated $60 billion a year is eventually collected, leaving a net shortfall of $381 billion a year — or about 14% of total taxes owed.

The agency estimated that $352 billion of the gross tax gap was the result of underreporting income, while $50 billion was due to underpayment and $39 billion was due to taxpayers not filing returns.

The latest figures are not markedly different from the agency’s revised estimates for 2008 through 2010, showing that the gross tax gap for those years was $394 billion and the net gap was $344 billion. Factoring in collections after enforcement efforts, the estimated share of taxes eventually paid is about 86% for both three-year periods, which is roughly in line with earlier estimates as well.

"Voluntary compliance is the bedrock of our tax system, and it's important it is holding steady," IRS Commissioner Chuck Rettig said in a statement. "Tax gap estimates help policy makers and the IRS in identifying where noncompliance is most prevalent. The results also underscore that both solid taxpayer service and effective enforcement are needed for the best possible tax administration."

Where the gap is largest: Third-party reporting and tax withholding are major drivers of voluntary tax compliance, the IRS says. The W-2 forms employers provide to the agency on wage earners make it harder for individuals to cheat and easier for the IRS to catch taxpayer mistakes. The IRS says that just 1% of income amounts subject to “substantial information reporting and withholding” is misreported. But for income subject to little or no reporting — such as that earned by proprietors of cash businesses — the rate of misreporting is 55%.

Putting the gap in perspective: The federal budget deficits in the years covered by the latest IRS report, 2011 through 2013, were $1.3 trillion, $1.1 trillion and $680 billion, so shrinking the $381 billion tax gap — it’s unrealistic to expect it to be eliminated completely — would have still left sizable deficits in at least two of the years. Even so, the net tax gap represents a sizable chunk of the $808 billion spent on Social Security in fiscal year 2013 or the $626 billion spent on defense and $492 billion spent on Medicare that year. And it’s larger than the $265 billion spent on Medicaid and the $221 billion paid in net interest costs.

Projecting the 2011-2013 numbers out — accounting for growth in the tax base and assuming all underlying ratios remain constant — Bobby Kogan, a Senate Budget Committee staffer, calculates that the tax gap for 2020 would be $615 billion and the total over the next decade will reach $7.8 trillion.

Boosting the IRS budget: The agency has seen its funding cut in recent years, with 2018 appropriations about 20% lower in inflation-adjusted dollars than the peak reached in 2010, and it has reduced both its workforce and audit rate over that time. It’s not yet clear how those cuts might have affected the tax gap in the years since 2013. More recently, lawmakers from both parties have sought to increase IRS funding and shrink the tax gap. The Senate Appropriations Committee this month advanced a proposal to boost IRS enforcement funding by $200 million.

For more details, check out the tax gap map below.