As NATO leaders meet in Wales today to coordinate response to Russia’s incursion of Ukraine, and amid calls to strengthen the alliance, U.S. and British officials are reportedly set to call for an increase in European defense spending to prove their commitment to the Cold War relic.

These pleas, expected to be made by President Obama and UK Prime Minister David Cameron, are among countless others made by British and American officials since the fall of the Berlin Wall. In the last five years, in the wake of Europe’s sovereign debt crisis and as the threat from Russia decreased, European defense budgets have declined 20 percent.

Related: Putin Wants Eastern Ukraine. Let Him Have It

"Russia's actions in Ukraine shatter that myth and usher in bracing new realities," Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel said in a June speech at the Woodrow Wilson International Center in Washington. “Over the long term, we should expect Russia to test our alliance's purpose, stamina and commitment." Hagel added that the Ukraine crisis was a “clarifying moment” for NATO.

However, all the crisis has made clear is that much of Europe still lacks the political will do increase defense budgets in order to meet the NATO membership requirement of at least two percent of GDP spent on defense. Only three countries in Europe - the UK, Greece and Estonia - meet this threshold.

Any hope that there would be a recommitment to this rule was seemingly dashed Wednesday night, when reports in the Canadian media indicated that neither Canada nor Germany would be willing to make the pledge.

“We are open to increasing military spending when and where it makes sense and in response to particular needs,” a senior Canadian government official told Canada’s National Post. “But the notion of setting an arbitrary target does not make sense.”

Related: A Radical Way for Ukraine to Fight and Defeat Russia

More troubling for Europe is Germany’s unwillingness to renew its financial commitment to Europe. According to the Post, German defense officials said that it’s not the percentage of GDP that matters, but the actual amount of money spent (Germany’s 2014 defense budget is $42.8 billion).

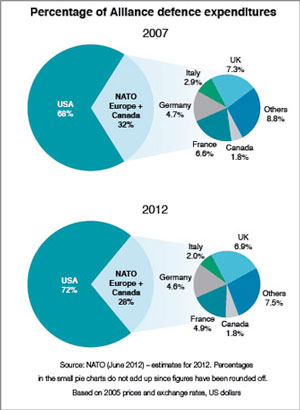

Without a new spending commitment from Europe, the United States would be left shouldering the burden for NATO. Obama said that “this is a moment of testing" for the alliance, as illustrated by the chart below.

Dan Hamilton, director of the Center for Transatlantic Relations at the John’s Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, said Germany’s reluctance provides the rest of Europe with the cover needed to shrink away from NATO obligations.

“A lot of countries hide behind Germany. [The Germans are] going to have to have a pretty forceful statement,” he said. “The question is what deeds follow the words.”

However, shifting German attitudes toward Russia -- the key to building political will within the Bundestag -- is not an easy task. At the start of the crisis, Germans were split over whether to back Putin or Obama. The downing of Malaysian Airlines Flight 17 nudged German Chancellor Angela Merkel to take a more forceful stance and call for tougher sanctions. Now, as the crisis appears to be abating, Germany’s long-term commitment to NATO remains a mystery.

Related: Cameron on ISIS: Tougher Talk But Still No Strategy

The German NATO delegation declined comment. The German embassy in Washington did not return a request for comment.

Olaf Boehnke, head of the Berlin office of the European Council on Foreign Relations, said that one of the reasons that it’s so difficult to build political will in Germany is that the German people want to think better of Russia.

“People desperately want to believe in the post-cold war Russia … which learned its lessons from history and transforms into a Western style democracy,” said Boehnke. “People over here don’t love Russia and my sense is, they don’t trust Putin, but they really want to believe that these worrisome days of confrontation between East and West are over.”

Steffen Dobbert, a journalist with the German newspaper die Zeit, said that close ties to Russia from within the German political establishment also make it difficult to build momentum to do more to counter Russia. He noted that former chancellor Gerhard Schröder is a close friend of Putin and is president of Nord Stream AG, the Gazprom pipeline set to deliver energy from Russia to Germany. He also said that the German left still sympathizes with Russia’s communist past.

“The left wing parties in Germany - the Free Democratic Party and much more Die Linke [the Left] - they have a past in a socialist system. That’s why they have very good connections to Russia,” Dobbert said.

He added that Germany’s history makes it citizens reluctant to condemn one side as good, and one said as bad.

“There is pluralism here,” he said. “Maybe tomorrow someone writes that Putin isn’t a bad guy.”

“It can’t be that easy,” Dobbert said of a simple black and white narrative on Russia in Ukraine. “There have to be two sides.”

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times

- The Israeli Solution for Kurdistan

- Obama Makes the Middle East Our New ‘Quagmire’

- If Kurds Fall, Chaos in Iraq and Abroad to Follow