Dr. David Fowler’s staff is scrambling to keep up with the surging stream of corpses flowing through the doors.

In his 15 years as Maryland’s chief medical examiner, Fowler has seen natural disasters, train crashes and mass shootings. Heroin- and cocaine-related homicides have plagued this city for decades. But he says he’s never seen anything that compares to the opioid epidemic’s spiraling death toll. As fentanyl, carfentanil and other deadly synthetic opioids seep into the illicit drug supply, it’s only getting worse.

Related: How West Virginia Became Ground Zero for the Opioid Epidemic

The recent surge in drug overdose deaths has created an unprecedented nationwide demand for autopsies and toxicology examinations, said Brian Peterson, president of the National Association of Medical Examiners, which accredits the forensic pathologists who perform death investigations.

Many medical examiners are working overtime and, in some places, they’re running out of refrigerated storage for bodies. When that happens, local officials typically borrow additional space at local funeral homes and hospitals, and in some cases, rent refrigerated trucks, he said. “Virtually every medical examiner’s office and toxicology laboratory in the U.S. has felt the impact of the opioid tsunami.”

In Maryland, homicides and fatal car crashes also are on the rise, creating far bigger caseloads for medical examiners than recommended by the national association. The concern is that performing more than the recommended limit of 325 autopsies in a year, in addition to other duties such as testifying in court, could result in errors.

“People are using drugs every day, but they died today instead of yesterday. Why? They might have had a heart attack, pneumonia or a stroke. Drugs are there but they may not be the cause of death,” Fowler said.

Related: US Death Rate From Heroin and Opioid Abuse Rages Out of Control

Over-reporting drug deaths could be just as harmful as under-reporting them, he said. “We could be missing something else that’s killing people.”

In April, Republican Gov. Larry Hogan approved the Maryland medical examiner’s request for three new forensic pathologists to help handle the additional workload. But after more than two months of searching for qualified candidates, none have emerged.

There are job openings all over the country and not enough forensic pathologists to fill them, Fowler said. “The sad thing is that when we find someone, we’ll probably be stealing them from somewhere else.”

No. 1 Killer

Nationwide, the drug overdose epidemic is now claiming more lives than both homicides and automobile accidents combined, and there were more fatalities from drug overdoses in 2015 than AIDS-related deaths during that epidemic’s peak in the 1990s. Drugs are the No. 1 killer of people under 50, and they are shortening the average American life expectancy.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s most recent count of drug overdose deaths was more than 52,000 in 2015, with at least 33,000 due to heroin, fentanyl, prescription painkillers and other opioids.

An early calculation of 2016 drug deaths by The New York Times estimates that overdose deaths were as high as 65,000 last year. That would be the largest one-year increase in history. Evidence from drug seizures and medical examiners’ reports suggests the death toll will be even higher this year.

Related: The White House Is Ignoring the Real Cause of the Opioid Epidemic

“It turns out that Narcan [an opioid overdose antidote] is not the miracle drug everyone thought it was,” Fowler said. “It works great for an overdose of heroin, but now with fentanyl you need three doses. With carfentanil you need six.”

The overdose victims are revived with Narcan, which blocks the effect of opioids. But the problem is that many refuse further medical attention, walk away, and later die. That’s because after about an hour the rescue drug stops working, but the potent opioids continue to suppress breathing, sometimes for as long as eight hours.

People who overdose on heroin, fentanyl and other synthetic opioids need to be taken to a hospital, and put on a respirator, Fowler said. Some may need multiple doses of Narcan. But in many cases, that’s not happening. An increasing number of the fatal overdose victims his staff investigates were rescued earlier the same day, he said.

Wide Variation

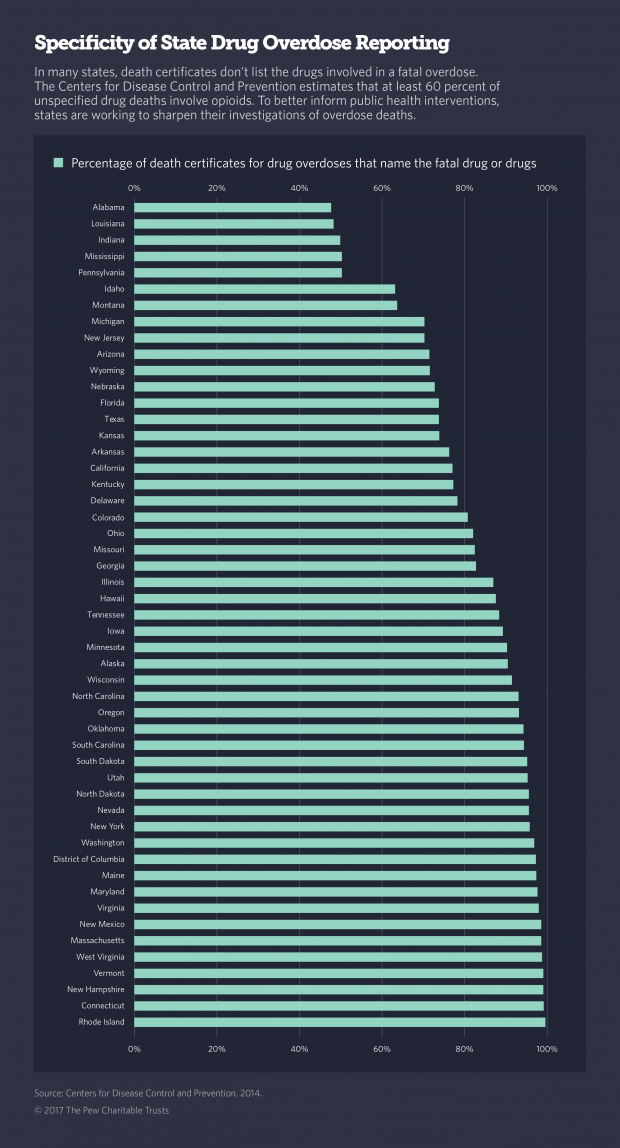

States vary widely in the accuracy, level of detail and timeliness of their death certificate reporting, which has created substantial information gaps for law enforcers, public health officials and epidemiologists attempting to defeat the opioid epidemic.

Maryland is one of only 15 states and Washington, D.C., that fund a unified statewide medical examiner system to ensure that consistent and accurate death investigations, including autopsies, are performed on all people whose deaths are caused by injury, homicide or suicide, and those that are sudden, accidental, untimely, suspicious or not attended by a doctor.

Related: How Medical Marijuana Can Help Reduce the Opioid Crisis

Eleven states only have locally elected coroners — with no required training, no state money, and typically slim budgets — deciding when an autopsy is needed, usually with local police. They then call on freelance pathologists to perform an autopsy using local hospital or outpatient facilities.

Eighteen states have a mix of elected coroners and trained medical examiners, and five states have county or district medical examiners. Coroners are often sheriffs or funeral home professionals, while medical examiners are almost always doctors with additional training in forensic pathology.

Drug overdoses, typically classified as drug intoxication deaths by medical examiners, are considered accidental deaths and in most jurisdictions require an autopsy and toxicology examination. In this opioid epidemic, however, that rule is being debated within the profession because of the shortage of forensic pathologists available to perform autopsies.

Fowler maintains an autopsy should be done in nearly every apparent drug death. “If a 25-year-old is found dead with a tourniquet on his arm and a syringe in his hand and there are witnesses, then maybe you don’t need an autopsy,” he said. “But in just about every other case you do.”

No End in Sight

The front of Maryland’s gleaming new medical examiner facility leans slightly forward on one of Baltimore’s quieter downtown streets. Its lobby doors are locked and the six-story glass and brick building is under 24-hour surveillance. “Drug lords have been put in the penitentiary for life because of the work we do here,” explained Bruce Goldfarb, special assistant to Fowler.

When the 120,000 square foot facility was built, in 2010, for $54 million, it was meant to have enough growing room to last until 2030. There’s still space to spare, Fowler said, but “we already have plans to add new autopsy rooms.”

Related: How the Opioid Crisis Could Derail the GOP Health Plan

On the third floor of the spotless, nearly silent building, an observation deck offers a view of the two main autopsy rooms a flight below, each equipped with eight stainless steel sinks and the sets of tools, scales and gurneys needed to dissect and analyze the bodies. There is also a separate biohazard autopsy room for badly decomposed bodies, along with cooling space for up to 400 corpses.

With a state-of-the-art toxicology laboratory on-site and 75 full-time employees, the Maryland examiner’s office can complete an investigation of a drug death within a week. Bodies are autopsied within 24 hours of entering the building and toxicology tests take three to five days, provided no new synthetic drugs are involved. There is no backlog.

In other parts of the country, toxicology reports can take six weeks or more, and bodies are sometimes stored in walk-in coolers for days before an autopsy can be performed. Bodies are then typically transported to a funeral home — or to a potter’s field, in cases where no family member claims the body.

In South Carolina, one of five states with a county coroner system, most jurisdictions don’t even have their own coolers, said Dr. Kim Collins, a medical examiner at Newberry County Memorial Hospital and a vice president of the national examiners’ association. When more bodies come in than local coroners can handle, they typically ask a nearby hospital or funeral home to store them temporarily, she said.

“There are so many deaths from drugs, and the workforce is so understaffed, and local coroners and pathologists are suddenly having to reach out to their toxicology friends to identify these new drugs. We don’t even know what we’re looking for sometimes, so it takes much longer to close a case, and then suddenly you have an onslaught of six more cases you weren’t expecting,” she said.

Nationwide, only about 500 trained medical examiners are at work, and a disproportionate number are nearing retirement age, the national association’s Peterson said. The job requires 13 years of training after high school including four years of college, four years of medical school, four years of residency in general pathology, and another year of forensic pathology.

More than a hundred jobs are open right now and more are opening up every month, Peterson said. The number of forensic pathologists nationwide is half of what is needed to handle the current volume of deaths, according to Peterson, and evidence suggests the number of drug deaths will keep growing.

But only 30 to 40 forensic pathologists are minted each year, and because salaries for medical examiners, which are mostly public employees, are so much lower than for general pathologists, many quit mid-career for more lucrative jobs in hospitals. “The situation in forensic pathology is truly dire,” Peterson said.

In some places, including Maryland, student loan forgiveness and signing bonuses are under consideration to attract more medical examiners. But in the meantime, Fowler said, medical examiners are going to do what they have to do under state laws.

Collins agreed: “Medical examiners will go above the limit on autopsies to serve the public even if they’re going to lose their accreditation. We’re absolutely going to investigate every drug case, and we can’t just say ‘I’m not going to investigate a dead baby or a gunshot death’ either. You do it to serve justice. You can’t not do it.”

This article originally appeared on Stateline. Read more from Stateline:

Louisiana Adopts Landmark Criminal Justice Reforms

The U.S. Meat Safety System Just Turned 101—It’s Time to Modernize