Although it may be hard to imagine now, at some point in the not-too-distant future the 2024 election will be over and a new government will take over in Washington. No matter who is in power, the new president and Congress will quickly face some major fiscal issues, driven by the expiration at the end of 2025 of the tax cuts for individuals Republicans enacted in 2017.

Republicans are calling for the tax cuts to be extended, which the Congressional Budget Office has warned would cost some $4.6 trillion over 10 years. Democrats say they want tax cuts for low- and middle-income households to remain in place, while allowing the cuts for high-income households to expire as part of a series of changes designed to reduce the budget deficit.

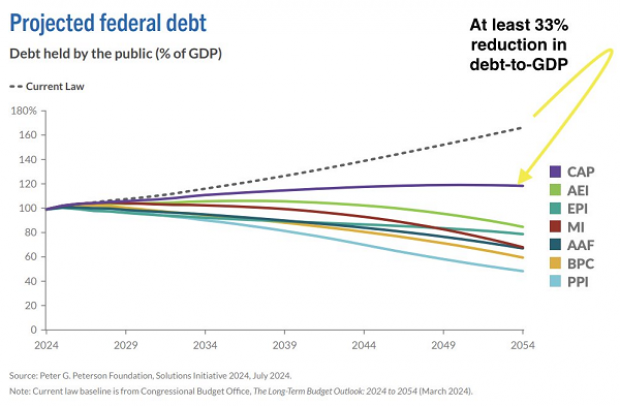

The debate over taxes and revenues will inevitably touch upon the long-term trajectory of the debt, which the CBO estimates will increase significantly over the next decades in the absence of new policy, reaching record levels as a percentage of gross domestic product as soon as 2027 and then moving up from there.

On Tuesday, the Peter G. Peterson Foundation published proposals from seven think tanks across the political spectrum that address the issue of rising debt. The proposals lay out seven paths policymakers could take to prevent the debt from growing relative to the size of the economy. (The Fiscal Times is an editorially independent organization funded by the late Peter G. Peterson and his family.)

As the chart below indicates, all the proposals reduce the projected debt-to-GDP ratio by at least a third by 2054, relative to the current baseline. Most of the proposals go even further, reducing the debt-to-GDP ratio below current levels over three decades.

How do they do it? Howard Gleckman of the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, which scored the proposals, says all of the think tanks agree that some new tax revenues are required, but there is less agreement on how much or how to raise those revenues.

The think tanks on the right — the American Action Forum (AAF), the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) and the Manhattan Institute (MI) — prefer to emphasize spending reductions to free up funding for deficit reduction. The think tanks on the left, the Center for American Progress (CAP) and the Economic Policy Institute (EPI), and those closer to the center — the Progressive Policy Institute (PPI) and the Bipartisan Policy Center (BPC) — more typically call for more tax increases to help fill in the fiscal gap.

The think tanks agree that Social Security, which faces a funding shortfall in about a decade, is in need of reform. All of the groups provide ways to extend the program’s solvency for another 30 years, with most calling for an increase in the current cap on earnings subject to the payroll tax, which could raise between $670 billion to $1.2 trillion over 10 years. Raising the retirement age was cited by four of the think tanks, a move that could produce $121 billion in savings over 10 years.

In terms of health care, three of the think tanks called for streamlining Medicare Parts A, B and D into a single program, saving as much as $100 billion in costs. The conservative think tanks called for converting Medicare into a premium-support plan and capping costs in Medicaid on a per capita basis.

In terms of taxes, six of the groups called for raising the level of tax revenue as a percentage of GDP, relative to the current baseline. The conservative groups generally held taxes below 20% of GDP, while the liberal groups pushed taxes above that level to fund more extensive social spending. The Economic Policy Institute was the most aggressive, calling for tax revenues to rise to 31.3% of GDP by 2034 — nearly twice the level described by the right-leaning American Enterprise Institute.

The bottom line: There’s more than one way to improve the nation’s fiscal trajectory, and detailed plans have already been laid out, awaiting lawmakers’ attention. While there is widespread agreement that the federal government needs more revenues, there is likely no easy way through the politics involved in changing the tax code.

“Politics is the main obstacle to getting this done,” says The Washington Post’s editorial board. “But the Peterson report shows where Congress and the next president could realistically begin.”