On January 1, sales and use of recreational marijuana became legal in the state of Colorado. Washington State and the nation of Uruguay will follow later this year. Other states such as Oregon and California have ballot initiatives scheduled that may legalize marijuana there as well. It is a virtual certainty that if these initial experiments work out, as was previously the case with casino gambling, it will spread rapidly to other states.

Several factors appear to be at work in the drive to legalize recreational marijuana. First is the abject failure of the war on marijuana, which, surprisingly, began right at the moment when prohibition of alcohol was ending.

RELATED: POTENOMICS--THE BIRTH OF THE LEGAL WEED INDUSTRY

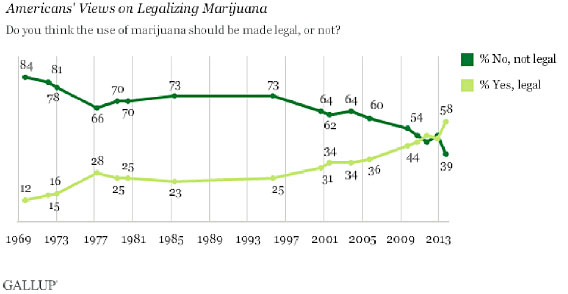

Polls are unanimous in showing rising support for marijuana legalization, especially among younger Americans. Opponents are gradually dying off, literally, according to an April 2013 Pew poll.

In October, Gallup found that support among all Americans for legalization exceeded maintenance of the status quo for the first time since it began asking the question in 1969.

Importantly, support for marijuana legalization is not driven mainly by those who use it now or would like to; that is, it’s not just an issue of self-interest. Rather, it is because non-users no longer see marijuana as a gateway drug that automatically leads to the use of more serious drugs, according to a December Associated Press/Gfk poll. In fact, a rising percentage of people believe that legalization of marijuana will actually curb the use of harder drugs--17 percent now from 10 percent in 2010.

RELATED: 7 BARELY LEGAL POT PRODUCTS FROM A BUDDING INDUSTRY

Perhaps the dominant factor driving marijuana legalization is the desperate search for new revenue by cash-strapped state governments. The opportunity to tax marijuana is potentially a significant source of new revenue, as well as a way of cutting spending on prisons and law enforcement. The California Secretary of State’s office, for example, estimates savings in the hundreds of millions of dollars from both factors. The following summary is from a proposed state ballot initiative in California (No. 1617).

Summary of estimate by Legislative Analyst and Director of Finance of fiscal impact on state and local government: Reduced costs in the low hundreds of millions of dollars annually to state and local governments related to enforcing certain marijuana-related offenses, handling the related criminal cases in the court system, and incarcerating and supervising certain marijuana offenders. Potential net additional tax revenues in the low hundreds of millions of dollars annually related to the production and sale of marijuana, a portion of which is required to be spent on education, health care, public safety, drug abuse education and treatment, and the regulation of commercial marijuana activities.

Interestingly, anti-tax crusader Grover Norquist has given his blessing to taxes on marijuana, since it is an extension of existing taxes on cigarettes and liquor applied to a comparable commodity, rather than a new tax per se.

The potential revenue obviously depends a lot on details that are presently unknown—the ultimate price of legal marijuana, which could be substantially lower than the present price in illegal markets; the tax rate; the elasticity of demand for marijuana; and the extent to which states and the federal government permit a legal marijuana market to function without crippling regulation.

RELATED: 11 SURPRISING THINGS THAT ARE TAXABLE

A 2010 Rand Corporation report found that many financial estimates of marijuana legalization are simply unknowable since existing research is limited by the availability of data for a market that has long been illegal. A new Rand report on marijuana use in the state of Washington now estimates that usage may be 2 to 3 times greater than previously estimated.

It is not surprising that revenue considerations should be critical in the marijuana legalization movement. That was previously the reason why cigarettes were not banned until the 1920s despite a strong nationwide movement to do so. In the wake of Prohibition, governments simply needed cigarette tax revenue too badly. And when Prohibition ended, the need for new revenue after the Great Depression decimated government budgets was a driving force.

Indeed, according to author Daniel Okrent, expectations of the revenue from taxing legal liquor were so great in 1932 that some people thought it might permit the repeal of income taxes. It’s worth remembering that in 1900, taxes on alcohol and cigarettes constituted half of all federal revenues. Indeed, the only reason Prohibition was possible in the first place was that the income tax established in 1913, which was greatly expanded by World War I, would replace the revenue lost from the liquor tax after Prohibition.

The principal opponents of marijuana legalization are industries that presently benefit from it being illegal. For example, it is reported that the beer industry invested heavily against a 2010 marijuana legalization initiative in California that ultimately failed. Other vested interests that currently benefit from the outlawing of marijuana include police unions, the private prison industry, prison guard unions, and pharmaceutical companies fearing that low-cost legal marijuana might replace profitable high-cost prescription drugs such as Vicodin.

I don’t have the data to prove it, but I have long suspected that virtually every economist favors the legalization of marijuana and probably most hard drugs as well--regulated as has long been the case with alcohol and, increasingly, tobacco. The famous economists Milton Friedman, Gary Becker and Robert Barro have written many columns advocating legalization, and I am not aware of a single economic analysis in opposition to legalization. I think most economists believe it’s just a repetition of the mistake of Prohibition.

I am doubtful that the legalization of marijuana or any other currently prohibited drug is likely at the federal level any time soon. There is no movement in Congress to do so and politicians such as former New Mexico governor Gary Johnson and Baltimore mayor Kurt Schmoke who supported the idea got nowhere. It will happen at the grass roots level in states that permit voters to propose initiatives and at the federal level only after we have enough years of experience to have a good understanding of the consequences. It may take another 20 years, but eventually it will happen.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: